There are videos of McGrew and Erik Manning criticizing the Minimal Facts approach, but I decided not to interact with those as responding to videos takes even more time than responding to written articles. This is do to having to transcribe verbally spoken words into text form when quoting snippets for the sake of critique. Fortunately, McGrew has not one, not two, but three articles on this subject. They can all be found at “What’s Wrong With The World”. In this article, I’ll be responding to her article titled “Minimal Facts VS. Maximal Data”. I’ll respond to McGrew point by point.

How Dare Someone Like Bill Craig Imply Christians Don’t Believe The Gospels Are Reliable

I was somewhat disappointed with the first few paragraphs of this article. There’s too much text to quote verbatim without bogging down the reader, so I will summarize and leave it to the reader to click on Dr. McGrews link to fact check if I’ve represented her accurately. Before ever getting to any alleged historigraphical or epistemological problems, she first rightly describes The Minimal Facts Approach as being an approach that uses a few core data points, all of which are granted by the majority of scholars, even skeptical ones, and that the argument does an end run around the issue of reliability. Oddly, she refers to William Lane Craig as a minimalist despite his insistance that he doesn’t use a minimal facts method [1]See The Reasonable Faith Podcast, “Objection To The Minimal Facts”, May 6th 2018 — … Continue reading However, due to the fact that her article appears to be written in 2015, Craig’s podcast episode came out in 2018, and the fact that structurally, Craig’s approach and Habermas’ are very similar, I can’t blame McGrew for thinking that they’re one and the same. [2]My friend Caleb Jackson who wrote a book on the resurrection called “Undead: A Historical Investigation Into The Most Famous Miracle Of History” calls Dr. Craig’s approach … Continue reading There’s a quote from Craig that McGrew takes issue with. Craig writes “Evangelicals sometimes give lip service to the claim that the Gospels are historically reliable, even when examined by the canons of ordinary historical research; but I wonder if they really believe this. It really is true that a solid, persuasive case for Jesus’ resurrection can be made without any assumption of the Gospels’ inerrancy.” [3]As quoted in “Minimal Facts VS. Maximal Data” by Lydia McGrew, http://whatswrongwiththeworld.net/2015/02/minimal_facts_are_not_enough.html

I honestly have no clue why Craig implied that Christians don’t believe in the historical reliability of the gospels when examined by the canons of ordinary historical research. McGrew evidently linked to a place on ReasonableFaith.org where Craig had said this, but the link only takes me to the front page of his Question Of The Week articles. I cannot say whether more context would have illumined what Dr. Craig meant. If I am allowed to speculate, Dr. Craig might have meant that he suspects most Christians only affirm the reliability of the gospels due to their pre-commitment to biblical inerrancy. And despite using “Reliability” and “Inerrancy” as interchangable terms, he’s simply saying that most Christians in the world believe the gospels are reliable out of a theological belief than historical commitment. If that’s true, then I think we could agree. Most Christians around the world, if they’ve even heard of apologetics, haven’t taken the time to look into the arguments and evidence as to why Christianity is true. But for those like Craig Blomberg, Lydia McGrew, Tim McGrew, Titus Kennedy, J. Warner Wallace, Lee Strobel, and even that dastardly evolution believing annihilationism affirming apologist Evan Minton, all deeply have studied the evidence and believe the gospels ARE reliable, even wholey apart from theological commitments. If I were convinced tomorrow that The Bible made a few mistakes in what it intended to teach (in the gospels, or anywhere in the canon for that matter), I’d still believe the gospels are reliable documents. Indeed, as Craig himself said in the aforementioned podcast episode, he himself affirms the reliability of the gospels.

But at the end of the day, I want to know what any of this has to do with the legitimacy of The Minimal Facts Approach as a method. It just feels like a rant that probably should have been written elsewhere.

Scholarly Consensus Doesn’t Agree That Appearances Of Jesus were physical as in the gospels.

Dr. McGrew then quotes Gary Habermas and Michael Licona on the importance of scholarly consensus in employing a minimal facts method. At one point, Habermas is quoted as saying something I’ve said rather recently just in different words. “When discussing the Minimal Facts, I have always purposely included notes at each juncture that list representative numbers of skeptics of various stripes who still affirm the data in question. This is a significant methodological procedure that serves more than one purpose. Among others, it assures the readers that they are not being asked to accept something that only conservatives believe, or that is only recognized by those who believe in the veracity of the New Testament text, and so on. After all, this sort of widespread recognition and approval is the very thing that our stated method requires.” [4]quoted in ibid. I was recently asked “If you’re just going to argue for these points, why does scholarly consensus matter?” And there are three reasons;

First, If you’re a scholar debating another scholar, you might not even need to defend these points at all. You can just skip to examining what explanation best accounts for facts. If someone like Licona debates an Ehrman or a Ludemann who already accepts the crucifixion and appearances, then they can just skip this and debate the best explanation of the facts; be it a naturalistic theory, or maybe when they try to hide behind David Hume. That’s a strength.

Secondly, As Habermas said, this can make a big impression on the nonbeliever. “Wait, it isn’t just super conservative evangelical scholars who accept these facts? Skeptics like me do too? Almost ALL of them? Hmm…well, maybe I shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss what you have to say.” Scholarly consensus doesn’t establish the facts AS facts – to say so would be to commit the bandwagon fallacy. But knowing that even hard hearted skeptics acknowledge these as facts might make the skeptic at least a little more open to hearing you out. In my own writings on The Minimal Facts argument, I hardly mention the scholarly consensus at all. I mention it at the beginning because I want to specify that I am indeed using a Minimal Facts method and what criteria makes a minimal fact, a minimal fact. And maybe at the end of giving 1, 2, or however many arguments time alots me for a given fact, I’ll say “In light of these reasons, hopefully you can see why even critics grant it.” I don’t say it quite like that in currently existing writings, but that is the spirit behind my handful of skeptic quotations at the end of each article in my “Evidence For The Resurrection Of Jesus” series. In some conversations on other parts of the internet, I may something like “Most scholars – even skeptics – accept these. Here are a few reasons that convinced them.”

Thirdly, related to the issue of persuasion, it can be impressive to see how far you can go when your hands are tied only to what skeptical New Testament scholars will allow. Indeed, for someone like McGrew, she could honestly use this as a talking point if she weren’t so against The Minimal Facts method. “Look at how much can be established using a piddly amount of data. Now, I am claiming we have much more than this. If this is how strong the case is when using a small set of data points, imagine how strong the Maximalist case must be!” Sort of a modern day argument from the lesser to the greater if you will.

The Minimal Facts Method Cannot Get You To A Physical Resurrection

McGrew quotes William Lane Craig arguing for the minimal fact of the postmortem appearances to the disciples. Dr. Craig writes “First, the resurrection appearances. Undoubtedly the major impetus for the reassessment of the appearance tradition was the demonstration by Joachim Jeremias that in 1 Corinthians 15: 3-5 Paul is quoting an old Christian formula which he received and in turn passed on to his converts According to Galatians 1:18 Paul was in Jerusalem three years after his conversion on a fact-finding mission, during which he conferred with Peter and James over a two week period, and he probably received the formula at this time, if not before. Since Paul was converted in AD 33, this means that the list of witnesses goes back to within the first five years after Jesus’ death. Thus, it is idle to dismiss these appearances as legendary. We can try to explain them away as hallucinations if we wish, but we cannot deny they occurred. Paul’s information makes it certain that on separate occasions various individuals and groups saw Jesus alive from the dead. According to Norman Perrin, the late NT critic of the University of Chicago: “The more we study the tradition with regard to the appearances, the firmer the rock begins to appear upon which they are based.” This conclusion is virtually indisputable.” [5]quoted in ibid. Dr. Craig goes on to say “At the same time that biblical scholarship has come to a new appreciation of the historical credibility of Paul’s information, however, it must be admitted that skepticism concerning the appearance traditions in the gospels persists. This lingering skepticism seems to me to be entirely unjustified. It is based on a presuppositional antipathy toward the physicalism of the gospel appearance stories.” [6]again in ibid.

Immediately after using these two quotes, Dr. McGrew writes \\“When the architects of the minimal facts approach speak of a vast scholarly consensus on the “appearances” experienced by the disciples, they do not mean a consensus on the physical-type experiences recounted in the gospels. To those aspects of the stories, Craig acknowledges that many scholars still actually have an antipathy, though he (correctly) suspects that this is based on an ideological rather than a scholarly objection.

The weakness of what the minimal facts approach is claiming about the disciples’ experiences is further confirmed by Craig’s discussion of Wolfhart Pannenberg. Here is more on Pannenberg’s view from Craig:

I don’t think that Pannenberg’s objection to the appearances is based on naturalism or a bias against miracles. He is already committed to miracles in affirming the empty tomb. Rather, I think it would be exegetical, frankly. He is convinced by Grass’ exegesis of 1 Corinthians 15 that when Paul talks of a spiritual body, what he is talking about is an immaterial, invisible, unextended body. Therefore, the Gospel appearance stories are late legendary developments that represent a kind of materializing of the original, primitive, spiritual experiences. The original experiences were just these visions of Jesus. It would be similar to Stephen’s vision of Jesus in Acts 73. When Stephen is being stoned, he sees the heavens open and he says, “I see the Son of Man in the heavens.” Nobody else saw anything, but Stephen saw this vision of Jesus. And I think that Pannenberg would say that that is similar to what the original resurrection appearances were. They were these visionary events and then they got corrupted and materialized and turned into the Gospel appearance stories, which are very, very physicalistic.”\\

She goes on to assert that with the information Minimal Facts users use, we cannot conclude that Jesus physically rose from the dead. Unless we use her favorite method, at most we can conclude is that the disciples saw something that looked like Jesus. Maybe it was a ghost. Maybe it was some form of a hallucination (bereavement, or otherwise). She says that without the gospel records, we can’t be sure whether these were fleeing appearances or long, drawn out coversations with Jesus in which he did things like eat and drink, as we see him doing in the gospels.

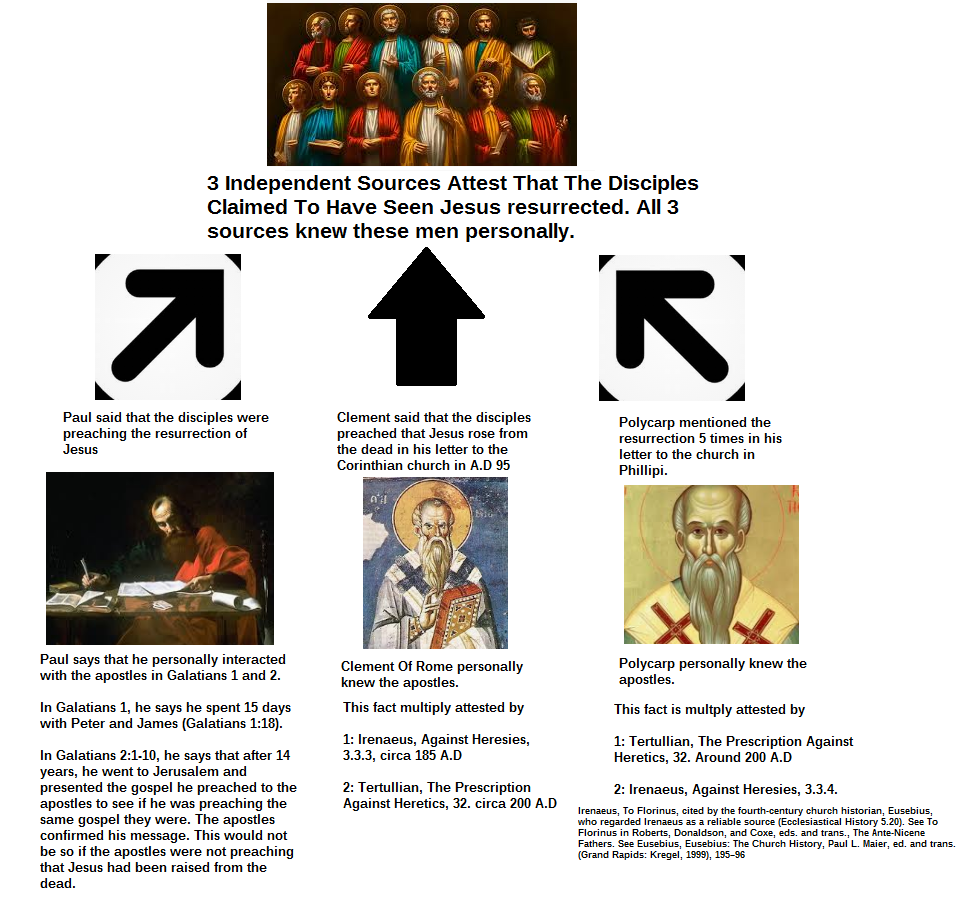

Although she seems to be somewhat aware of how Habermas responds to such alternative explanations, she makes statements that amount to “Yeah, but, your response could be so much stronger if you’d just use the gospels”. And she also seems to remark that Habermas’ way of dealing with the ghost or hallcuination theories go beyond the scholarly consensus. Maybe they do, and maybe they don’t. I had read that most psychologists agreed that mutliple hallucinations on multiple occasions to people of different mindsets was impossible. That doesn’t seem to be a disputed data point. And we get multiple group appearances from 1 Corinthians 15:3-8 along with a few individual appearances. Jesus appeared to Cephas, then the twelve, then 500 individuals, then to James, then all of the disciples, and finally Paul. There are least 3 independent group appearances here. And I don’t get this idea that we don’t or can’t use the gospels in a minimal facts method, but in my writings I do appeal to the group appearances in the synoptics and John to corroborate the early creed. This way I can make a multiple attestation argument. The appearances are early, come from eyewitness testimony (which is at least derived from the testimony of Paul’s interactions with the apostles, and Clement and Ignatius’ reports of what the disciple’ taught) but it’s also multiply attested. It’s multiply attested even without the gospels as you have Paul’s, Clement’s, and Polycarp’s testimony that the disciples were preaching the risen Jesus. And the fact that Polycarp and Ireneaus personally knew the disciples and told us what they believed is multiply attested by Tertullian and Ireneus. See the infograph below.

The details of this can be read at blog “The Evidence For Jesus’ Resurrection Part 5: Fact (3) – The Postmortem Appearances To The Disciples”. With regards to appealing to the disciples (which as a “minimalist” I’m allegedly not supposed to do), I simply cite that these sources report physical resurrections as well, and that they do so independently. There doesn’t seem to be any reason to think they took their material on Paul’s creed (unless you presuppose apostolic authorship from Matthew and John, which I do affirm but don’t grant for the sake of argument).

The major point here is that, regardless of how much time the appearance of the postmortem appearance lingered, multiple group appearances on multiple different occasions is improbable to the point of being impossible. In fact, a psychologist whom Lee Strobel interviewed in preparation for his book “The Case For Christ” said that this many people having a hallucination at exactly the same time would “be a bigger miracle that the resurrection itself!” [7]Strobel, Lee. 1997. God’s Outrageous Claims: Discover What They Mean for You. p. 215, Zondervan

In their book “The Case For The Resurrection Of Jesus” [8]Gary Habermas, Michael Licona, “The Case For The Resurrection Of Jesus”, pages 105-106, Kregel, Gary Habermas and Mike Licona tell of Navy Seals who were enduring through Hell week. At one point, the seals reported starting having hallucinations one night while they were paddling in a raft at night. They all hallucinated at the same time, but they did not have the same hallucination. They all had different hallucinations. One of them said he saw an octopus come out of the water and wave at him. Another said he saw a train coming towards them on the water. Another said he saw a wall that they would crash into if they persisted in paddling. When the octopus, the train, and the wall were pointed out to the rest of the group, no one saw any of the things except the one who pointed the thing out. They were all hallucinating, but they were having different hallucinations. So, even if on the off chance that all of the disciples, Paul, and James were in the frame of mind to hallucinate, it’s still unlikely that they’d have the same hallucination. Like the Navy Seals, they’d likely all have different hallucinations, perhaps only one of them being Jesus.

Moreover, even if the impossible did occur, and the minds of all these different groups of people produced hallucinations of Jesus, that would still leave the empty tomb unaccounted for. What happened to Jesus’ body? Why is it gone? You see, unlike Michael Licona who NEVER uses The Empty Tomb nowadays (unlike in the previously cited pop level book), I ALWAYS use the empty tomb. Even if I don’t defend the crucifixon (maybe my interlocutor is well read enough to grant it), I’ll at least include the empty tomb and the postmortem appearances to the disciples. Never have I not used the empty tomb even in my most minimal of minimal facts presentations. This is why there’s some debate over where William Lane Craig and myself even use a minimal facts at all, but merely something similar to it. See footnote number 2. All subjective or objective vision hypotheses trip over the empty tomb. Perhaps this is the real reason why the empty tomb only has a 75% acceptance rate among New Testament scholars; because the skeptical ones realize they have to account for Jesus’ missing body. And hallucination theories and ghost theories just don’t do that and ergo fail on the grounds of inadequate explanatory scope.

But does such as response as I have given (which is heavily drawn from “The Case For The Resurrection Of Jesus” Habermas and Licona wrote in 2004) go beyond the boundaries set by the minimal facts method as McGrew contents? Does it break the Minimal Facts Approach rules, so to speak?

First of all, I don’t really care. All I really care about is being able to defend the resurrection of Jesus without me and my interlocutor getting bogged down on issues like alleged contradictions, historical mistakes, authorship, et. al. [9]I remember one December back in 2012, I was arguing with a skeptic on Twitter/Twitlonger. I was using the reliability approach. I ended up getting side tracked having to argue for things like … Continue reading If you want to call this a Minimal Facts Approach, A Moderate Facts Approach, or if you want to leave it nameless, it doesn’t really matter to me. But the way I’ve been defending the resurrection since discovering Habermas and Licona’s book in 2014 has made me 100 times more effective at defending the truth of Christianity to skeptics. I have even convinced a small number to become Christians, and I hope to add to that number.

Secondly, I have always interpreted the scholarly consensus rule to refer to the facts themselves, not in evidence used to refute naturalistic explanations. The Minimal Facts Approach is a two step approach; first you present the facts to be explained. Then you decide on which explanation best accounts for those facts. It has always been my understanding that the “Don’t use data the critics won’t accept” rule really only applies to that first step. Perhaps I am mistaken about that.

I would also agree with McGrew that multi-censory experiences, touching and eating with Jesus, hearing him speak, etc. would make a case against subjective visions even more problematic. However, whether a response can be even stronger than it already is hardly seems relevant as to whether a response is sufficient to refute an opposing theory. Take The Swoon Theory for example. I have seen apologists simply use David Strauss’ argument and not even appeal to any of the medical evidence that refutes the idea that Jesus could have survived.

Non-Christian David Strauss explains that “It is impossible that a being who had stolen half dead out of the sepulchre, who crept about weak and ill and wanting medical treatment… could have given the disciples the impression that he was a conqueror over death and the grave, the Prince of life: an impression that lay at the bottom of their future ministry.” [10]Strauss, David. The Life of Jesus for the People. Volume One, Second Edition. London: Williams and Norgate. 1879. 412.

The response could definitely be made stronger by pointing out how severe the pre-crucifixion scurging was, that even when Josephus’ friends were given medical treatment, only 2 out of the 3 survived, that Jesus was suffering hypovolemic shock on the way to the crucifixion, et. al. You can go into all of that, but is it not a powerful logical argument that Strauss gives sufficient enough to put the swoon theory to rest? Sure, you can pile on more reasons to discount it, and when I address the Swoon Theory, I usually do, but I see no reason why they would have to. Why is it not sufficient to point out the improbability of even one group of men at one time having a shared hallucinations (like the aforementioned Navy Seals) much less multiple groups of people on multiple occasions? Why is that not enough? Does Mcgrew have some data on even 10 second long group appearances that she’s not sharing with us? As I sometimes say in joking manner when talking about hallucination theories “If you have 10 druggies all doing LSD, what are the odds they’re going to see the same dragon? Especially on multiple different occasions?” Whether they say the dragon for 5 seconds, whether he sticks around long enough to even say “Hi” or whether he raids all the beer out of the fridge, you just don’t have this kind of thing occurring in the psychological literature. If 12 men are do see a dragon, and there’s also burning buildings in their wake, it might be time to contact National Geographic! Bereavment Hallucinations are even worse, especially when Paul’s experience is brought in. Paul wouldn’t have been grieving Jesus’ death. He thought Jesus was a heretic and blasphemer and that Christians should be destroyed! Until, that he, he had an encounter that he reports in his epistles and is corroborated independently by the book of Acts.

Well, what about the idea that Jesus was a ghost? This is sometimes called an “Objective Vision” as opposed to a subjective vision.

There actually is a way to refute the idea that the risen Jesus was just a spooky spectre without appealing to the gospels. First, In the pre-Pauline creed that Paul cites in 1 Corinthians 15, we have a strong indication of a physical resurrection. “…Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day according to the scriptures”. Whoa! Stop right there! Christ “was buried” and “was raised”? If Paul had a ghostly non-physical resurrection in mind, and if those whom he got this creed from had that in mind, what is the importance of mentioning the burial? Creeds had to be short in order to contribute to easy memorization, so the odds that they put Jesus’ burial in there, if the burial were an unimportant detail are not good. It had to have been important.

Jesus “died”, “was buried”, “was raised”. The creed contra-juxtaposes Jesus’ burial with His resurrection. This contra-juxtaposition implies that the body that went down in burial came up in resurrection. The body of Jesus was buried, but then it got up and walked out of the tomb. Died → Buried → Raised. I think this heavily implies that a physical resurrection was in view.

Secondly, there’s a cultural context argument to be made. World renowned New Testament scholar N.T Wright wrote a thick book called The Resurrection Of The Son Of God (2003), and in the first half of the book, he spends an enormous amount of time surveying ancient pagan, Jewish, and Christian literature from a variety of geographical locations. He concludes that in the ancient world, Pagans, Jews, and Christians alike understood the Greek word “anastasis” (resurrection) to mean bodily resurrection. Wright also demonstrates that they were aware of ghost stories and hallucinations and that in all accounts of spooky spectres showing up, not once were these ever described as anastasis. Space obviously does not permit me to delve into all of those sources here, but you can check out N.T Wright’s book for yourself if you want to fact check me.

And there are other reasons for discounting the Ghost Jesus interpretation. I go into several of these in chapter 8 of my book “My Redeemer Lives: Evidence For The Resurrection Of Jesus”.

So, what is the point I’m making? The disciples were claiming that Jesus was resurrected. Not that he simply appeared to them. Even the 1 Corinthians 15 creed calls what happened to Jesus a “resurrection”. He was raised, and after he was raised, he appeared to all these people. Granted, 1 Corinthinans 15 doesn’t give us details about the nature of these appearances. Dr. McGrew is completely right about that. We can’t make arguments like “We know Jesus wasn’t a ghost because he ate fish in front of his disciples, and ghosts can’t eat. Ghosts aren’t physical”. Nevertheless, the fact that all across the early epistles everyone refers to this as a resurrection, and no one seems to interpret it otherwise, suggests that the disciples must have experienced something during those times of postmortem appearances which convinced them that Jesus had actually physically come back. If we don’t appeal to the gospels, we can’t know what those details are. True. But we can at least say at minimum “The apostles interpreted these appearances as physical appearances of a raised Jesus. Something about these appearances must have lent themselves to such an interpretation.”

It’s even more startling when you get into the lack of expectation that anyone would be raised prior to the eschaton (which N.T Wright also talks about in The Resurrection Of The Son Of God). Oh yeah, and you an empty tomb to explain.

Conclusion

Dr. Lydia McGrew is an excellent apologist, and I’m glad she’s devoted so much time and research to studying the New Testament, and defending its reliability. I hope it’s clear from this article that I don’t mean to disparage her or her work. However, I think her crusade against The Minimal Facts Aprpoach is misguided. Here, I have only responded to one out of three of the articles in which she has critiqued the method. I will put others up shortly.

For me, I think Christians who go into apologetics should be able to use both methods. It’s always better to have more than one argument for a conclusion. I would like for The Minimal Facts and Maximalist Methods to be able to co-exist in the apologetics community as they used to.

References

| ↑1 | See The Reasonable Faith Podcast, “Objection To The Minimal Facts”, May 6th 2018 — https://www.reasonablefaith.org/media/reasonable-faith-podcast/an-objection-to-the-minimal-facts-argument |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | My friend Caleb Jackson who wrote a book on the resurrection called “Undead: A Historical Investigation Into The Most Famous Miracle Of History” calls Dr. Craig’s approach “The Moderate Facts Approach” and is what he uses in his own book. This is because Dr. Craig always uses the burial and empty tomb of Jesus. Most of his data points are accepted by either most or a small majority of skeptical scholars, but he has never explicitly dubbed his method. According to Caleb, the Moderate Facts Approach is actually the method I employ. I go back and forth in my mind as to whether or not I agree with him. Do I usually employ some middle ground method between minimialism and maximalism? To an extent it doesn’t matter. A rose by any other name is just as sweet. |

| ↑3 | As quoted in “Minimal Facts VS. Maximal Data” by Lydia McGrew, http://whatswrongwiththeworld.net/2015/02/minimal_facts_are_not_enough.html |

| ↑4, ↑5 | quoted in ibid. |

| ↑6 | again in ibid. |

| ↑7 | Strobel, Lee. 1997. God’s Outrageous Claims: Discover What They Mean for You. p. 215, Zondervan |

| ↑8 | Gary Habermas, Michael Licona, “The Case For The Resurrection Of Jesus”, pages 105-106, Kregel |

| ↑9 | I remember one December back in 2012, I was arguing with a skeptic on Twitter/Twitlonger. I was using the reliability approach. I ended up getting side tracked having to argue for things like Luke’s Census, the astrophysical viability of the Bethlehem Star, whether Herod really slaughtered Bethlehem babies or whether Matthew just made that up. We got so lost on whether the gospel records were viable that the conversation ended without us making much headway. Why this interlocutor of mine chose these specific errors to use, I can only guess. It was early December, so maybe the accounts of the birth narrative were fresh in his mind. |

| ↑10 | Strauss, David. The Life of Jesus for the People. Volume One, Second Edition. London: Williams and Norgate. 1879. 412. |

“Since Paul was converted in AD 33, this means that the list of witnesses goes back to within the first five years after Jesus’ death. Thus, it is idle to dismiss these appearances as legendary.”

The Bible itself disproves this assumption. Legends and rumors developed in first century Palestine no less quickly than they develop in any other century of human existence. Luke chapter 9 states that Jews in Jesus’ day believed he was John the Baptist raised from the dead. John had only been dead for a few weeks!

—“Paul’s information makes it certain that on separate occasions various individuals and groups saw Jesus alive from the dead.”

What did all these people see? Please give us just two undisputed, corroborating eyewitness testimonies of people witnessing the same post-mortem sighting of a walking, talking body. You can’t.

“Dr. Craig goes on to say “At the same time that biblical scholarship has come to a new appreciation of the historical credibility of Paul’s information, however, it must be admitted that skepticism concerning the appearance traditions in the gospels persists. This lingering skepticism seems to me to be entirely unjustified. It is based on a presuppositional antipathy toward the physicalism of the gospel appearance stories.”

I will admit that atheist skeptics have a bias against the supernatural, but the post mortem appearance stories in the Gospels fail even the basic requirements for eyewitness testimony:

–the documents are unsigned and never explicitly state the name of the author. Can you imagine presenting unsigned and unnamed “testimony” to a modern court of law?

–no two Appearance Stories describe the same postmortem appearance! Christians frequently compare the four Gospel accounts to four eyewitnesses to the same car crash. The problem is, the four Gospels never describe the same car crash!

–investigators always want to make sure that the eyewitnesses to an event do not have access to the testimony of other eyewitnesses prior to giving their own testimony. Allowing witnesses to preview the testimony of others taints their testimony. Even Christian scholars admit that Luke and Matthew had access to Mark, and John may well have had access to all three Synoptic Gospels.

The evidence for this alleged event fails even basic legal standards of testimony!

“And we get multiple group appearances from 1 Corinthians 15:3-8 along with a few individual appearances. Jesus appeared to Cephas, then the twelve, then 500 individuals, then to James, then all of the disciples, and finally Paul. There are least 3 independent group appearances here. And I don’t get this idea that we don’t or can’t use the gospels in a minimal facts method, but in my writings I do appeal to the group appearances in the synoptics and John to corroborate the early creed. This way I can make a multiple attestation argument. The appearances are early, come from eyewitness testimony (which is at least derived from the testimony of Paul’s interactions with the apostles, and Clement and Ignatius’ reports of what the disciple’ taught) but it’s also multiply attested. It’s multiply attested even without the gospels as you have Paul’s, Clement’s, and Polycarp’s testimony that the disciples were preaching the risen Jesus.”

Nope. If no two people describe the same postmortem appearance of Jesus you do not have multiple attestation. You simply have a lot of claims of a lot of people seeing something odd at different times and places. That’s it. All these separate sightings are unconfirmed, therefore, they could simply be hysteria or legends.

“The major point here is that, regardless of how much time the appearance of the postmortem appearance lingered, multiple group appearances on multiple different occasions is improbable to the point of being impossible. In fact, a psychologist whom Lee Strobel interviewed in preparation for his book “The Case For Christ” said that this many people having a hallucination at exactly the same time would “be a bigger miracle that the resurrection itself!” [7]”

Educated counter-apologists like myself know that no two people can have the same, simultaneous hallucination. An hallucination can explain an alleged appearance to one person but not to a group. Most skeptics believe that the group sightings recorded in the Early Creed involved illusions or false sightings (seeing someone in the distance and thinking it is Jesus). Modern Christians claim to see appearances of another resurrected person, the Virgin Mary, when all anyone else sees is the sun moving in and out of the clouds. Groups of people can experience illusions: seeing something real in the environment but interpreting it as something else.

“All subjective or objective vision hypotheses trip over the empty tomb. Perhaps this is the real reason why the empty tomb only has a 75% acceptance rate among New Testament scholars; because the skeptical ones realize they have to account for Jesus’ missing body. And hallucination theories and ghost theories just don’t do that and ergo fail on the grounds of inadequate explanatory scope.”

Wrong. You assume the empty rock tomb of Arimathea is historical fact. Most skeptics, including Bart Erhman and Gerd Luedemann reject its historicity. There is zero evidence for a rock tomb. Between the writing of the Gospels and the fourth century, there is no mention of a known rock tomb of Jesus until the mother of Constantine “found” it when looking for locations to build a great church in Jerusalem! Christians ASSUME that Christians living in Jerusalem had always known the location of this tomb. Really? Prove it! Assumptions, assumptions, assumptions: the glue that holds together the Christian supernatural resurrection tale.

“Non-Christian David Strauss explains that “It is impossible that a being who had stolen half dead out of the sepulchre, who crept about weak and ill and wanting medical treatment… could have given the disciples the impression that he was a conqueror over death and the grave, the Prince of life: an impression that lay at the bottom of their future ministry.” [10]”

Another assumption: that the alleged postmortem appearances occurred three days after Jesus’ burial. Apologists assume the Gospels are historically accurate…to prove the Gospels account of the Resurrection historically accurate. Silly. So it is entirely possibly (but highly, highly unlikely) that Jesus swooned on the cross and was placed in the tomb alive. He was then wisked out of the tomb by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus Saturday evening after sunset and nurtured to health for the next six months. Six months after his public execution and burial, Jesus briefly shows up to see the disciples while they are fishing on the Sea of Galilee, before high tailing it out of Palestine to the Far East. Highly improbable, but much more probable than the revivification and postmortem appearances of a corpse, in the minds of atheists, Jews, and Muslims.

“If Paul had a ghostly non-physical resurrection in mind, and if those whom he got this creed from had that in mind, what is the importance of mentioning the burial?”

Most skeptics (who are not mythicists) believe Jesus was buried…somewhere. Jews didn’t allow bodies to lie around above ground. At some point in time the Romans would have taken the remains down from the cross and buried them or allowed the Jews to bury them. So his remains were most likely put in the ground (buried). Most skeptics believe Jesus was most likely buried in a mass grave with the bodies of other crucifixion victims. Do you need a verifiable empty tomb to believe a bodily resurrection has occurred? This is a critical question. Think about it. If you believe that Jesus has appeared to you, must you go to his grave and verify it is empty to believe he has been resurrected? If the grave is close by, probably yes. But what if his grave site is unknown? What if his grave is a mass Roman pit with dozens of other bodies and the Romans never disclosed its location to the disciples or anyone else? Even if you do know where the mass grave is, how would you know Jesus’ body was missing among all the other bodies?? People believe dead people appear to them all the time and have been having these dead person sighting experiences for thousands of years. The claim about Jesus was novel because it claimed that Jesus was making appearances in his revivified body. No one, pagan or Jew, had ever heard of one person being bodily resurrected. Does the novelty of a claim make it true? No. However, one must remember that “bodily resurrection” was not unheard of. Many Jews believed it would one day occur to all righteous people. The Christian belief in one individual’s resurrection (Jesus) was simply a new twist to an established Jewish concept. This is how new sects occur: they take an established concept in the mother religion and give it such a new twist that is unacceptable to the mother religion. Christianity is not unique.

“He concludes that in the ancient world, Pagans, Jews, and Christians alike understood the Greek word “anastasis” (resurrection) to mean bodily resurrection. Wright also demonstrates that they were aware of ghost stories and hallucinations and that in all accounts of spooky spectres showing up, not once were these ever described as anastasis.”

—Most skeptics believe that very early on Christians came to believe that Jesus had been bodily resurrected. Question: Must one see a resurrected body to believe that a bodily resurrection has occurred? According to the Bible itself, the answer is no. In Acts chapter 26 the author says he is recording Paul’s account of his Jesus appearance experience which triggered his conversion to Christianity. Does Paul ever say that he saw a resurrected BODY? No. So why did Paul convert to “The Way” which taught that Jesus had been bodily resurrected if he had not seen a resurrected body??? This is evidence that first century Jews did not need to see a resurrected body to believe in the Resurrection. This is crucial!!! If Paul could believe in the bodily resurrection of one individual due to bright lights and hearing voices, why couldn’t this explain the “appearances” which occurred to the original eyewitnesses among the Twelve? If Paul can hallucinate an appearance of Jesus why couldn’t some of the Twelve have hallucinated an appearance of Jesus? Now, hallucinations could only account for individual appearances. Group hallucinations are impossible. What about the group appearances in the Early Creed? Answer: illusions. Groups of believers saw a bright light and what they believed was a voice (it was only the brief whistling of the wind) and believed it was an appearance of Jesus. The appearances are so easy to explain, dear Christians. Why can’t you see it?

“It’s even more startling when you get into the lack of expectation that anyone would be raised prior to the eschaton (which N.T Wright also talks about in The Resurrection Of The Son Of God). Oh yeah, and you an empty tomb to explain.”

If the story of Paul is correct, the crucifixion of Jesus occurred three years prior to his conversion. During that time he was persecuting the Jerusalem church. He must have known everything about them, including their claims and beliefs. Paul was a smart guy. He was educated. He was a pharisee. He would know better than the average Jew that no one in the history of Judaism had ever claimed to see a resurrected body. No one had ever claimed that one person could be bodily resurrected prior to the general resurrection of the righteous dead. Yet over 500 devout Jews were claiming that a resurrected body had appeared to them!!! Why wasn’t Paul convinced of their claims? If the uniqueness of this claim proves it to be true, as NT Wright claims, why didn’t the eyewitness testimony of over 500 people convince educated Jews like Saul of Tarsus of the reality of Jesus’ resurrection??? Answer: Educated first century Jews obviously did not consider the eyewitness testimony of a bunch of mostly illiterate Galilean peasants claiming to see a resurrected body to be credible evidence. And how did Paul explain Jesus’ empty tomb? It was right there in Jerusalem. Paul could have gone and examined it to make sure it was empty. Paul could have checked with the Sanhedrin to verify it was the correct tomb. Paul could have verified with the Sanhedrin that the tomb had been sealed and guards had been placed outside of it…and yet it still was found empty three days later. Paul could have verified that the Temple curtain tore in half that day. That a great earthquake happened that day. That the sky turned black for three hours. That dead people had been shaken out of their graves to roam the streets and chat up old friends. But no, PAUL DOES NOT BELIEVE with all this evidence! Why, dear Christians? Why??? If the evidence is so good and so strong that you believe it should convince any open-minded skeptic today, why didn’t the same evidence convince Paul just months/a few years within Jesus’ death? That is the big question you need to answer.

“For me, I think Christians who go into apologetics should be able to use both methods. It’s always better to have more than one argument for a conclusion. I would like for The Minimal Facts and Maximalist Methods to be able to co-exist in the apologetics community as they used to.”

The Minimal Facts Method fails because there are only THREE minimal facts, not five. Skeptic scholars do not believe the Empty Tomb Story is historical. Most believe Jesus was buried in an unmarked common grave or pit. The Maximal Facts Method fails because assuming the Gospels are historically reliable does not make them so. No public university history textbook states that the Gospels are historically reliable accounts of the life and death of Jesus. Why? Is it because they hate Christianity? No. It is because the majority of historians do not believe that the Gospels meet the standards for historical reliability. Period. Now, apologists like yourself will claim that you have done extensive research on the subject and you know more than the experts. This may appeal to the blue collar crowd but you will be laughed at by educated non-Christians. Educated people respect expert consensus opinion. That is why most educated non-Christians, like myself, believe that Jesus truly existed and believe the Three Minimal Facts. That is also why most educated people, like myself, do not believe that the Gospels are historically reliable sources. The educated, technologically sophisticated world depends on respect for consensus expert opinion. It may not be perfect, but it is the most accurate measure of truth we have. You ignore this standard at your own peril, Evan.