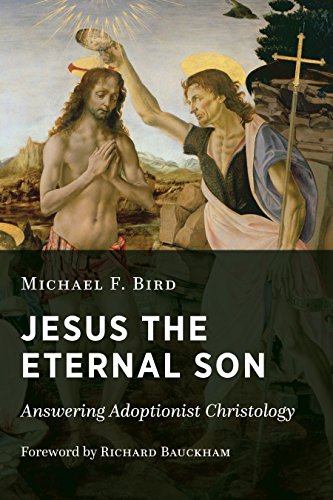

A thorough refutation of Adoptionist Christology. Bird makes his case from the ground up, arguing from the presuppositions of non-Christian scholars like Ehrman that the New Testament isn’t inspired. Bird DOES believe The New Testament is inspired, but most New Testament scholars who push adoptionism today do not. Ergo, not many references are made to books like the gospel of John or Philippians which (I THINK is one of the disputed Pauline epistles). The book progresses with Michael Bird looking at the proof texts adoptionist cite from Romans 1 and Acts 2 and shows how they do not reflect adoptionist Christology. One of several reasons is that the authors of Romans and Acts show a pretty evident Incarnational Christology in several other places in their texts. While “interpreting scripture in light of scripture” is a hermeneutical principle normally done even between biblical books, it is nevertheless a good idea to look all of what an author says. It’s one thing to say that in light of all of the biblical evidence for Jesus’ deity in the New Testament, an adoptionist reading of these few texts is probably wrong, it’s quite another to say that in light of what author X says throughout the SAME DOCUMENT, author X probably isn’t asserting adoptionist Christology here.

My favorite section was on the gospel of Mark. Michael F Bird debunks the notion that the divinity of Jesus should be interpreted against the backdrop of Roman Emperors becoming divine after death. For one thing, Bird shows that it was a highly contested practice rather than an uncontested norm. For another thing, the absolute monotheistic perspective of Mark shows that Mark would have considered it unconscionable to turn a mere mortal man into a god to rival Yahweh. The section on Mark is divided up into two parts. In the first part, he deals with emperor apotheosis. In the second part, he makes a positive case that the gospel of Mark had a high Christology, that Mark portrayed Jesus as God incarnate, and as the son of the Father even prior to His baptism (a place adoptionists assert was the place Jesus became God’s son).

After dealing with the biblical data and establishing persuasively, in my opinion, that Mark, Acts, and Romans are in concord with John and Nicea, he goes on to look at the extra biblical writings in the second century such as the Shepherd of Hermas to see when in fact adoptionist Christology DID develop. It didn’t develop with the apostles, so when did it come up? After a survey of the relevant texts, Michael Bird ends up concluding that adoptionist Christology wasn’t really a thing until near the end of the second century. Bird concedes that it’s possible this heresy existed even before then, but it cannot be drawn from any of the extant material that survives from the first century, and if nothing else, it definitely didn’t come from the biblical authors.

This is a book that I think every Christian Apologist should have in their library.

Discover more from Cerebral Faith

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A thorough refutation of Adoptionist Christology. Bird makes his case from the ground up, arguing from the presuppositions of non-Christian scholars like Ehrman that the New Testament isn’t inspired. Bird DOES believe The New Testament is inspired, but most New Testament scholars who push adoptionism today do not. Ergo, not many references are made to books like the gospel of John or Philippians which (I THINK is one of the disputed Pauline epistles). The book progresses with Michael Bird looking at the proof texts adoptionist cite from Romans 1 and Acts 2 and shows how they do not reflect adoptionist Christology. One of several reasons is that the authors of Romans and Acts show a pretty evident Incarnational Christology in several other places in their texts. While “interpreting scripture in light of scripture” is a hermeneutical principle normally done even between biblical books, it is nevertheless a good idea to look all of what an author says. It’s one thing to say that in light of all of the biblical evidence for Jesus’ deity in the New Testament, an adoptionist reading of these few texts is probably wrong, it’s quite another to say that in light of what author X says throughout the SAME DOCUMENT, author X probably isn’t asserting adoptionist Christology here.

My favorite section was on the gospel of Mark. Michael F Bird debunks the notion that the divinity of Jesus should be interpreted against the backdrop of Roman Emperors becoming divine after death. For one thing, Bird shows that it was a highly contested practice rather than an uncontested norm. For another thing, the absolute monotheistic perspective of Mark shows that Mark would have considered it unconscionable to turn a mere mortal man into a god to rival Yahweh. The section on Mark is divided up into two parts. In the first part, he deals with emperor apotheosis. In the second part, he makes a positive case that the gospel of Mark had a high Christology, that Mark portrayed Jesus as God incarnate, and as the son of the Father even prior to His baptism (a place adoptionists assert was the place Jesus became God’s son).

After dealing with the biblical data and establishing persuasively, in my opinion, that Mark, Acts, and Romans are in concord with John and Nicea, he goes on to look at the extra biblical writings in the second century such as the Shepherd of Hermas to see when in fact adoptionist Christology DID develop. It didn’t develop with the apostles, so when did it come up? After a survey of the relevant texts, Michael Bird ends up concluding that adoptionist Christology wasn’t really a thing until near the end of the second century. Bird concedes that it’s possible this heresy existed even before then, but it cannot be drawn from any of the extant material that survives from the first century, and if nothing else, it definitely didn’t come from the biblical authors.

This is a book that I think every Christian Apologist should have in their library.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

Discover more from Cerebral Faith

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.