Evan,

Evan,

As you have again mentioned The Ontological Argument, I’ve been examining it in detail, and I think I have pinpointed its fatal flaw.

You wrote in your first premise, “It’s possible that a Maximally Great Being (MGB) exists.” And you explained in your third premise that if an MGB exists, it must exist necessarily; otherwise, it wouldn’t be maximally great. We can’t avoid the property of necessary existence without describing a lesser, contingent being instead of an MGB. The word “necessarily” was there implicitly all along, so let’s include it explicitly. So we can combine these two premises into a single premise: “It’s possible that an MGB exists necessarily.” Equivalently, “It’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that an MGB exists.”

This equivalent statement about an MGB is now in the same format as statements we could make about necessary truths in mathematics and logic, such as the statement, “it’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4”.

By the definition of “necessarily true”, the statement “it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4” is equivalent to the statement “2+2=4 is true in all possible worlds”. Note that the statement “2+2=4 is true in all possible worlds” is either true in all possible worlds or false in all possible worlds. For in any possible world, the statement “2+2=4 is true in all possible worlds” is about the truth of “2+2=4” not just in that possible world or some other possible world, but in all of them.

By the definition of “possibly true”, the statement, “it’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4” asserts the truth of the statement “it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4” in at least one possible world. But we’ve already seen that if the statement “it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4” is true in at least one possible world, it is true in all possible worlds, and if it is false in at least one possible world, it is false in all possible worlds. So the statement “it’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4” is logically equivalent to “it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4”.

Using the same reasoning with “a MGB exists” in place of “2+2=4”, we see that the premise, “it’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that a MGB exists” is logically equivalent to “it’s necessarily true that an MGB exists”, which is by definition of the MGB logically equivalent to “it’s true that an MGB exists”, which means we are assuming in the premise the very thing we set out to prove, that an MGB exists. It’s a simple fallacy of begging the question shrouded in a complex detour into modal logic and talk of “greatness”.

Now, I used 2+2=4 both because it was the example you used of a necessary truth and because it can be proven true mathematically. But you could use in place of 2+2=4 any mathematical statement which is epistemically unknown but metaphysically certain to be either true or false in all possible worlds. For example, the statement “the Riemann Hypothesis (RH) is true”. We can’t tell at this time whether the RH is true in all possible worlds or false in all possible worlds (it must be one or the other), but that is because of the limits of our current knowledge. The truth or falsehood of the RH is an epistemic rather than a metaphysical possibility.

Likewise, whether the MGB is a metaphysical necessity or a metaphysical impossibility is an open epistemic question. My intuition tells me that there are possible worlds where no thinking beings exist, whereas I assume your intuition tells you such worlds are impossible. It must be one or the other, but by begging the question, the Ontological Argument sheds no light on the matter.

D. J.

———————————————————————————————————-

———————————————————————————————————

I’m glad you’re taking so much interest in the Ontological Argument, D.J, as I find it’s one of the best arguments for the existence of God out there, which is why I included it in my book

Inference To The One True God: Why I Believe In Jesus Instead Of Other Gods and it’s yet-to-be-released revised version;

The Case For The One True God: A Scientific, Philosophical, and Historical Case For The God Of Christianity.

Your objection is in a nutshell that The Ontological Argument is question begging. It assumes in its first premise the conclusion. Obviously, if the conclusion of an argument is one of the very premises of the argument, it’s logically fallacious. However, I don’t think that The Ontological Argument commits that fallacy. The first premise “It is possible that a Maximally Great Being exists” is simply a statement about whether the conception of a Maximally Great Being is possibly instantiated or not. As even most atheist philosophers will tell you, the soundness of the argument really depends on this first premise. It goes, the rest of the premises just fall like dominoes. The only way to show this premise false is to show that the concept of a Maximally Great Being is a logically incoherent concept like a square circle or a married bachelor.

The first premise doesn’t say that a Maximally Great Being does exist, just that the concept of a Maximally Great Being is a coherent concept. It’s something that could exist, unlike a married bachelor or one ended stick. Of course, a Maximally Great Being is defined from the outset as a necessarily existent Being who is omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, etc. What the other premises in the argument do is unpack the logical entailments of conceding that an MGB is possibly instantiated.

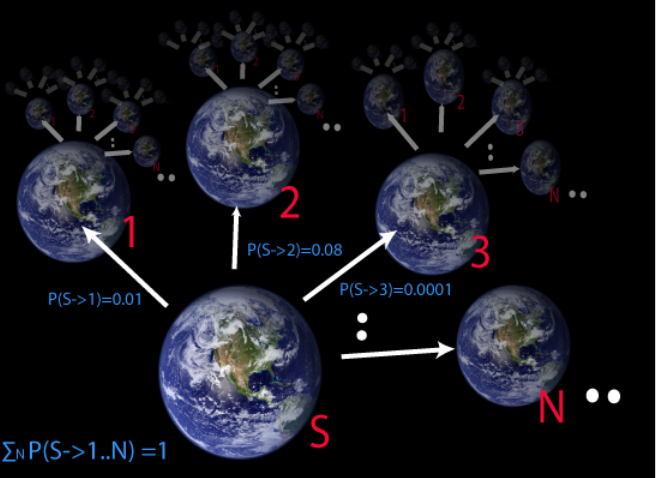

The logical entailment of such a concession is that there is a possible world in which an omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent, morally perfect, necessary being exists. But, it isn’t possible for necessary beings not to exist, then that follows that there’s no possible world in which the statement “An MGB does exist” is true or even possibly true. But in that case, that means an MGB exists in the actual world, since the actual world is a possible world. To deny the argument’s conclusion, you must either argue that necessary existence is not a greater property than contingent existence (Therefore, an MGB can exist in some possible worlds and not exist in others), or else show that an MGB is on par with square circles and married bachelors (i.e is logically impossible).

To use mathematical illustrations again, think of the argument this way.

1: It is possible that 2 + 2 = 15

2: If it is possible that 2 + 2 = 15, then 2 + 2 equals 15 in some possible world.

3: If 2 + 2 = 15 in some possible world, then it equals 15 in every possible world.

4: If 2 + 2 = 15 in every possible world, then it equals 15 in the actual world.

5: Therefore, 2 + 2 = 15 in the actual world.

6: Therefore, 2 + 2 = 15.

The argument is not question begging. It is merely asking whether the first premise is an actualizable state of affairs. In this case, we’d say no. There’s no way 2 and 2 going to make 15. Therefore, we’d deny the truth of the first premise as incoherent nonsense, making the whole argument garbage. However, if you do grant the truth of the first premise, then the rest simply follow since mathematical truths are necessarily true.

By contrast, consider if you change “15” to “4”. That is possibly instantiated. And since mathematical truths are necessary truths, it’s true in all possible worlds including the actual one.

You wrote: “”It’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4″ asserts the truth of the statement ‘it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4’ in at least one possible world. But we’ve already seen that if the statement ‘it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4’ is true in at least one possible world, it is true in all possible worlds, and if it is false in at least one possible world, it is false in all possible worlds. So the statement ‘it’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4’ is logically equivalent to ‘it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4′”.

I think your flow of thought was sound until you said “So the statement ‘it’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4’ is logically equivalent to ‘it’s necessarily true that 2+2=4′” I would disagree. I would say instead that the statement “It’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that 2 + 2 = 4” logically entails the statement “It’s necessarily true that 2+2 = 4. The concession of one entails the truth of the other. So if you want to deny the statement “It’s necessarily true that 2 + 2 = 4”, you must deny that “It’s possibly true that it’s necessarily true that 2 + 2 = 4” is a logically coherent statement.

The only real way to deny that a Maximally Great Being exists in the actual world is to say that the very concept of a Maximally Great Being is incoherent from the getgo. Just as I’d refute the argument above that 2 and 2 make 15 by showing that the first premise isn’t even possible.

William Lane Craig could perhaps say it better: Note: For readers unfamiliar with modal operators, “◊” means “it is possible that” and “□” means it is necessary that.” ◊□G stands for “It is possible that an MGB exists” and □G stands for “It is necessary that an MGB exists”.

“To say that ‘Possibly, a maximally great being exists’ is, indeed, logically equivalent to saying that ‘Possibly, it is necessary that a maximally excellent being exists.’ But these statements do not mean the same thing. It is the meaning of a statement that is relevant to its epistemic status for us, not its logical entailments. A statement may seem true to us even though we are quite unaware of its logical implications. It is, therefore, a mistake to say that “’possibly necessary’ is the same thing as ‘necessary,’” if by ‘is’ you mean ‘means.’ So it is a mistake as well to think that because ◊□G ↔ □G, the first premise of the argument ‘reduces’ to □G. It’s not a matter of reduction but deduction! The whole point of the ontological argument is to show that in asserting the possibility of the existence of a maximally great being one has committed oneself to its actual existence. The nature of a deductive argument is that the conclusion is implicit, stashed away, as it were, in the premises, waiting to be made explicit by means of the logical rules of inference. One typically believes that ◊□G without first believing that □G; at least one needn’t first believe that □G and then on that basis infer that ◊□G. One’s modal intuitions may support the belief that ◊□G, and then one may realize that that is logically equivalent to and so entails that □G, and so one comes to believe that a maximally great being exists.”

If you have any questions about Christian theology or apologetics, send Mr. Minton an E-mail at CerebralFaith@Gmail.com. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a Christian or Non-Christian, whether your question is about doubts you’re having or about something you read in The Bible that confused you. Send your question in, whatever it may be, and Mr. Minton will respond in a blog post just like this one.

I’m glad you’re taking so much interest in the Ontological Argument, D.J, as I find it’s one of the best arguments for the existence of God out there, which is why I included it in my book Inference To The One True God: Why I Believe In Jesus Instead Of Other Gods and it’s yet-to-be-released revised version; The Case For The One True God: A Scientific, Philosophical, and Historical Case For The God Of Christianity.

I’m glad you’re taking so much interest in the Ontological Argument, D.J, as I find it’s one of the best arguments for the existence of God out there, which is why I included it in my book Inference To The One True God: Why I Believe In Jesus Instead Of Other Gods and it’s yet-to-be-released revised version; The Case For The One True God: A Scientific, Philosophical, and Historical Case For The God Of Christianity.