We often talk of human beings having free will. In fact, I wrote an article giving 5 arguments for why human beings have it. I have the freedom to choose to eat healthily or to eat junk food, I have the freedom to watch Doctor Who on a Saturday evening or watch Pokémon. But we scarcely ever think about God’s free will. Does God have free will? Not according to one blogger; Vexen Crabtree. In this blog post, he goes on to give 5 arguments for why he thinks God does not have free will. It is the goal of this article to address those arguments and show why they are unsound.

Argument 1: God Does Not Have Free Will Because He Is Omniscient.

Crabtree writes “If you are all-knowing, you know your future actions, what choices you will make, and you cannot change them otherwise your knowledge would be wrong, and you wouldn’t be all-knowing. An omniscient being has no free will to choose actions; all its actions are predetermined.” and Crabtree goes on to give an illustration “There is a light switch on the wall; God may either turn it on, or leave it off; but, since God already knows the future, God knows that he will turn it on. That is part of his knowledge. But what if God exercises freewill, and chooses not to turn it on. Is this possible?”

I heard Dan Barker give this same argument in his debate with Richard G. Howe at The National Conference On Christian Apologetics. The argument here is that if at T-1, God knows He will do A at T-10, then once T-10 comes around, it is impossible for Him to choose non-A. Why? Well, He foreknew His own actions. He foreknew that at T-10, He would choose A. If God decided to choose non-A, then God would be wrong at T-1 since His foreknowledge contained the proposition “I will choose A at T-10”. It seems then, that if God knows the future, He cannot choose other than He chooses.

The problem with this argument is that it commits a modal fallacy which I’ve addressed elsewhere regarding God’s foreknowledge of our future free decisions, and this problem has been pointed out by Dr. William Lane Craig in his book The Only Wise God (pages 72-73). The argument can be expressed in syllogistic form like this

1: Necessarily, if God foreknows He will do X, then God will do X.

2: God foreknows that He will do X.

3: Therefore, necessarily, God will do X.

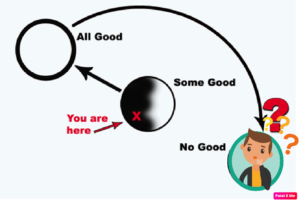

The problem with this syllogism is that while both premises are true, the conclusion does not follow. What follows from the two premises is not that God necessarily will do X, just that He will do X. X could be different. God could foreknow that He will do Y instead. If X were different, then God’s foreknowledge would be different.

For example, if God chose to simply teleport the Israelites to the other side of the Red Sea, rather than parting it for them to cross, God would foreknow “I will teleport the Israelites to the other side of the Red Sea”. But if God chose to part the Red Sea, then His foreknowledge would not contain the proposition “I will teleport the Israelites” but it would contain the proposition “I will part the Red Sea” instead.

While God’s foreknowledge is chronologically prior to His choices, God’s choices are logically prior to God’s knowing them. God’s knowledge of free choices (be they His own, or ours) are contingent facts which could very well be different, and if they were to be different than God’s foreknowledge would be different. God’s foreknowledge would contain different content.

So, to return to Crabtree’s lightswitch analogy, God could have chosen to turn the light switch off, but if that were His choice, His foreknowledge would have contained that from eternity past. If God chose to leave the light switch in the On position, then that is what He would have foreknown from eternity past.

Argument 2: A Perfect God Has No Free Will

Crabtree’s next argument is that because God is morally perfect, He, therefore, cannot make any immoral or imperfect choice. If He cannot make any immoral or imperfect choice, then God does not have free will. If God can choose an immoral or imperfect choice, then He is not a morally perfect being. He wrote “Out of the possible options in a situation God always makes the best choice because it is perfectly benevolent. It cannot do something that is less moral or “good” than something else, because that would not be perfectly good, but merely second-best good. In every situation, God only has one choice: The most moral/good one.”

The problem with this argument is that it only shows that God doesn’t have the freedom to do evil, and I would agree with that. God is incapable of committing sins. Even The Bible says as much when it says “God cannot lie” (Titus 1:2). However, this doesn’t mean God cannot choose between two or more equally good options. For example, God could have chosen to create all life through separate, individual miracles, or He could have chosen to use an evolutionary process. Both options are good, as the end result is the same (i.e humanity comes into existence). He could have chosen to create over 6 24-hour days or over billions of years.

Jesus could have chosen to (A) Multiply bread and loaves, or (B) make slices of pizza rain down from Heaven, or (C) make manna fall from the sky, or (D) create up and running restaurants out of nothing and then make them disappear as soon as everyone was fed. All four of these options seem to be equally perfect for obtaining the end-goal that God the Son sought: feeding a large number of hungry people and doing it in a miraculous way.

Crabtree anticipated this response in his article, and charged that while God could choose between two equally good alternatives, this would make His choices “random”. My Response: not necessarily. God could have reasons for deciding to perform one action instead of another, and those reasons wouldn’t necessarily have to do with whether that action is morally superior or functionally superior to the alternative He chose not to take. Think of this analogy: When I’m picking out what outfit I want to wear, I may be faced with (A) wearing my Skillet “Awake and Alive” T-shirt, or (B) A Pokémon shirt. Both options are ontologically and morally equal1, and I can choose between them. However, my choice of one of the other need not be totally random. I could have reasons for choosing one instead of the other. If I choose A, perhaps it’s because I’m attending the annual Winter Jam concert and Skillet will be playing there, so I want to show my fandom via my t-shirt.

Although it’s a popular misconception, free will does not assert that one’s choices are random or don’t have reasons behind them. It just means you had it within your power to make an alternative choice. I may have a reason for picking out the Skillet shirt, but nothing internal or external to me forced me to wear that shirt. It laid within my power to wear a different shirt (what philosophers have termed “The Principle Of Alternative Possibilities” or PAP for short). Philosopher Robert Kane describes the PAP by saying “it is ‘up to us’ what we choose and how we act; and this means we could have chosen otherwise. . . This ‘up-to-us-ness’ also suggests that the ultimate sources of our actions lie in us and not outside us in factors beyond our control.” 2

Argument 3: A Moral God Has No Free Will

The argument is basically that God must be able to choose between good and evil alternatives in order to be considered moral, and if He can’t, then He’s “Amoral”. Crabtree likens God to a computer whose programming makes Him always choose the best option. So, a morally perfect God is incoherent because a morally perfect God would only choose one course of action, but if God is only able to choose one course of action, then He isn’t really a morally perfect God. He’s an Amoral God.

I’m not entirely convinced that God must be able to choose evil in order for Him to be considered a morally good being. God can simply have goodness and love as part of His nature and act accordingly.

But, you may say “Didn’t you argue elsewhere that in order for love to be true love, you must be able to choose not to love?”. Yes, but I only think this is true of humans, not God. “Isn’t that special pleading?” you might say “You make the love-requires-free-will rule for humans but exempt God.” An argument or assertion is only special pleading if the exception is made without rational justification. In this case, I think there is a rational justification for exempting God of the true-love-requires-freedom-not-to-love rule.

I draw on Perfect Being Theology here. God, by definition, is the greatest conceivable being.3 He has all properties required to make a being great and He has them to the greatest extent possible.

My take on this is that God’s love is actually greater than a human being’s love because while human beings can choose to love, God is necessarily love. As 1 John 4:8 and 1 John 4:16 state, “God IS love”. His very nature is love. Love is embedded in God’s ontological existence. It’s like fire. Fire is necessarily hot. It is in fire’s nature to be hot. In fact, it’s essential to God’s nature to be loving just as it is essential to fire’s nature to be hot. If God were not love, He would cease to be God. Just as if fire were to cease to be hot, it would cease to be fire. It would lack an essential property that makes it what it is.

I hold that it is greater to be necessarily loving than merely contingently loving. You are a greater being if you have love as part of your ontological essence than if you merely choose to love someone. So even though God doesn’t have a choice between good and evil, and between love and hate, that doesn’t mean that His love for us isn’t genuine love, and it doesn’t mean we can’t appreciate His kind acts.

Free will is required for human love to be genuine love because it is not an essential attribute of a human to be loving. You can be a hateful son of a gun and still be a human being. God cannot hate and still be God. God’s love is greater than mine because my love is a contingent choice while God’s love is a part of who He is. If love were an essential attribute of humanity (and it’s not), I wouldn’t argue that we need free will for our love to be genuine.

So when Crabtree asks “What is the point of saying that God is moral, if God cannot choose to do anything imperfect? How can it be a moral being, if it has no moral choices?” it is like asking “What is the point in saying fire is hot if fire cannot choose to do anything cold? How can it be a hot entity if it has no temperature choices?”

Argument 4: A Timeless God Cannot Have Free Will

First of all, I agree with Doctor William Lane Craig’s position that God was timeless apart from the creation of the universe but entered into time at creation.4 Space does not permit me to go into why Craig and I believe God entered into time upon creation, but this is one view available to the Christian. One doesn’t have to hold that God is permanently timeless. Therefore, this objection would, at most, be relevant to any thinking or choosing God did pre-Big Bang.

The problem with this argument is that a perfect and omniscient God doesn’t need to deliberate. Crabtree seems to imagine God as like a man sitting at his coffee table trying to figure out which destination would be the most cost-effective vacation. But an omniscient man would already know which one is the most cost-effective vacation. He would not need to deliberate. Deliberation only occurs in non-omniscient beings who are trying to figure things out. Being omniscient, God doesn’t need to figure things out. He didn’t need to figure out which feasible world would be the best one for Him to actualize (“Let’s see, should I actualize W-10 or W-100?”). He already knew.5

And I think the real question is not how God can make a free choice before time, but how God can make any choice prior to the creation of time, regardless of whether it’s free or causally determined. If time is the dimension in which cause and effect take place, and the realm where before and afters are possible, how can God choose to create time before time exists? One option is to say that God’s decision to create and God’s actual act of creation are not sequential. That is to say, God doesn’t think “You know, I’d like to make a universe” and then exercises His omnipotent power to bring all matter, energy, space, and time into being. God’s decision to create the universe and His act of creating could occur simultaneously. Therefore, God’s decision to create time takes place in the first moment of time. So, you don’t have a “moment before the first moment” as critics of the doctrine of creation sometimes say.

Argument 5: How Can The Creator Of Free Will Have Free Will?

Crabtree wrote “Did God create free will? How then does it itself have free will? If God created free will then God had no choice in doing so. It must have been predestined to create it. But what created that predestination? God couldn’t have created free will; and as God is the ultimate creator, if it didn’t create free will then it means that free will doesn’t exist, for itself or anything else. Questions and problems like these show that free will is not a valid concept within theism.”

To Crabtree’s credit, while I don’t think any of His arguments succeed, the first four were at least good objections and were well thought out, but number 5 is extremely poor. He reasons that if God created free will then that means that He somehow cannot have it Himself? How exactly does that follow? God created minds inside of angels and humans. Does that mean God is mindless? God created a moral compass inside of humans (Romans 2:14-15), does that mean that He has no moral compass Himself? God created humans with rational faculties. Does that mean God doesn’t have rational faculties?

God could have free will and then decide to create creatures who have that same ability to choose. The fact that God is the Creator of free will by no means entails that He cannot have free will Himself. It entails only that God did not create His own free will. God created everyone else’s free will.

Summary and Conclusion

1: The first argument commits a modal fallacy. For God to foreknow His own decisions does not entail that His decisions are fated to occur. God could have chosen to act differently. If He did, His foreknowledge would have been different.

2: God may not be able to choose between good and evil, but He can choose between various options that are in accord with His morally perfect nature. He can even choose between alternatives that reach the same end goal (e.g multiplying loaves VS. making manna fall from the sky).

3: Given that goodness and love are essential attributes of God, He need not be able to choose evil and hate in order for His good and love to be genuine or appreciated. Human beings need free will for our actions to be praiseworthy and valued because goodness and love aren’t essential attributes of humanity. You can be evil and full of hatred and you would still be human. God cannot be evil or full of hatred and still be God. God’s love is actually superior to human love for the very purpose that it’s a necessary part of who He is.

4: God doesn’t sort through data, trying to figure out what the best course of action is. Given that God is omniscient, He already knows what the right course of action is. I don’t think being in time is required for this. Crabtree said, “Choices require changes in mental states over time.” Not necessarily. God could have decided all of His choices from eternity past in a single intuition.

5: This argument is absurd. Just because God is the Creator of free will in created beings doesn’t mean He can’t have free will Himself.

God can have free will, and unlike Crabtree stated at the end of the article, God is not impossible.

—————————————————————-

Footnotes

1: By saying the shirts are ontologically equal, I mean that one shirt is not superior to the other one. They’re both T-Shirts. The only thing different about them is what’s printed on them. Just as two men are ontologically equal even though they may have different skin colors or hair colors.

2: Kane, Robert, John Martin Fischer, Derek Pereboom, and Manuel Vargas. 2007. Four Views on Free Will. Wiley-Blackwell. 5.

3: See St. Anselm’s work.

4: Craig, William Lane. 1978. “God, Time, and Eternity.” Cambridge University Press 497-503.

5: Doctor William Lane Craig made this same point in his article; Craig, WIlliam Lane. 2002. “God, Time, and Eternity.” Oxbridge Conference. Reasonable Faith. http://www.reasonablefaith.org/god-time-and-eternity.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

Discover more from Cerebral Faith

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I love Dr Craig. He's one of my favorite thinkers.

Is important to understand what he does, which is primarily combat the fallacies of lazy arguments in theology (besides his Christian mission).

I think he understands that Logic cannot solve all angles of a problem on subjects that can strain our imagination.

A profound question is…

Does God know *Why or How he exists?

It's a fascinating question that is probably a category error. I feel God seeing his own future actions is in the same league but making bold proclamations, like this Crabtree fellow, are embarrassing.

It reminds me of the weak anthropomorphic reasoning of Calvin & his cohorts. They picture how a super Man or super computer would act.

God is not just a lone super being that just happens to occupy a probability space. I Am is probably the only way to describe God without limitation.

So while you did an excellent job in refuting that objection I'll go where a professional respectable person cannot. That dude is sooooo little league :). God is infinitely greater than the question. It shows a childish lack of depth and simply serves to illustrate his biases cloud his thinking.

Hello Evan, quick question here.

I lean more towards the view that God exists timelessly since I also lean towards the B-theory of time (although this is not set in stone and I may change my mind in the future). That’s why I am a bit concerned with argument 4 here. I know you believe that God entered into time at creation but for the sake of discussion, let us assume that God exists timelessly even with creation. Can God still have free will even if He is timeless?

I’m not sure how often you respond to comments. Should I email you this question instead?

I don’t think a God outside of time could do much of anything. Any action He would take would be a before-after transition, and that’s only possible with time. Of course, B-theorist Christians have often said that God actualized all of His choices at once and imposed all of His various miracles on the block universe, so that He doesn’t have to act more than once. That would be consistent with free will because God could choose not to do that. However, it would seem we’d still have the issue of there being a before God acted, and an after God acted, unless we want to postulate that the universe is co-eternal with God (i.e God’s decision never underwent a transition, it just eternally was), which I find biblically and theologically problematic, though philosophically speaking, there’s no issue.

Thank you for your answer! That’s an interesting point you made there about God and B-theory of time. I used to be an A-theorist as well but the challenges it faces against science shook my confidence. The final nail in the coffin was when a B-theorist pointed out to me that to say that God changes alongside creation is absurd for God is unchanging. Now that we’re on the topic, I was wondering what your response to this would be. As I have mentioned, I do not mind changing my mind on this.

Verses such as James 1:17 also seems to point to the fact that God is timeless. Other verses that have been pointed out to me would be when Jesus said, “Before Abraham was, I am”. He could have chosen to say “I was” or other variations of “I am” which do not change the tenses to imply timelessness. Some B-theorists believe this is Jesus claiming to be outside of time.

I am aware that there are some philosophical problems with the B-theory of time but it seems to be what fits with Scripture. I think you would disagree of course and I would be interested to hear why. Maybe I might come to see that I am in fact wrong.

I don’t view immutability the way some Christians do (for example, Thomists). Some view of God’s divine immutability or changelessness seem to extreme to me that I wonder how they don’t logically entail that God is some cosmic statue unable to do anything. I do think God is changeless because The Bible says as much. However, *in what way* is God changeless? I think William Lane Craig and J.I Packer have the accurate view of immutability. This is what Dr. Craig said in his Defenders Class

.

—https://www.reasonablefaith.org/podcasts/defenders-podcast-series-2/s2-doctrine-of-god-attributes-of-god/doctrine-of-god-part-10

.

So given the understanding of changelessness that I hold to, there would be no problem for God to go from being a timeless being to being a temporal being once He creates the universe. Anymore than it would be a problem for God to change from the status of not being the Creator of anything to being the Creator of everything.

.

Speaking of William Lane Craig, he gives a powerful defense of the A Theory of time in his book “Time and Eternity”. I highly recommend that you check it out.