In this article, I’d like to explain what my theological epistemology is. Epistemology is the study of knowledge; what we know, how we know, how we can be sure our knowledge is really justified true belief and not just a false belief. And, moreover, it is the studies of the methods we use to arrive at knowledge. What is it that grants us justification for our beliefs? Epistemology even asks questions such as “Can we choose what we believe?” and that gets into an interesting debate over views called Direct Doxastic Voluntarism VS. Indirect Doxastic Voluntarism. When it comes to these types of matters, especially when it concerns one’s Christian faith and worldview, different Christians take different approaches. This blog post will not be an exhaustive assessment of all such views, but I will simply state how I approach arriving at theological knowledge.

The Magisterial Use Or Ministerial Use Of Reason?

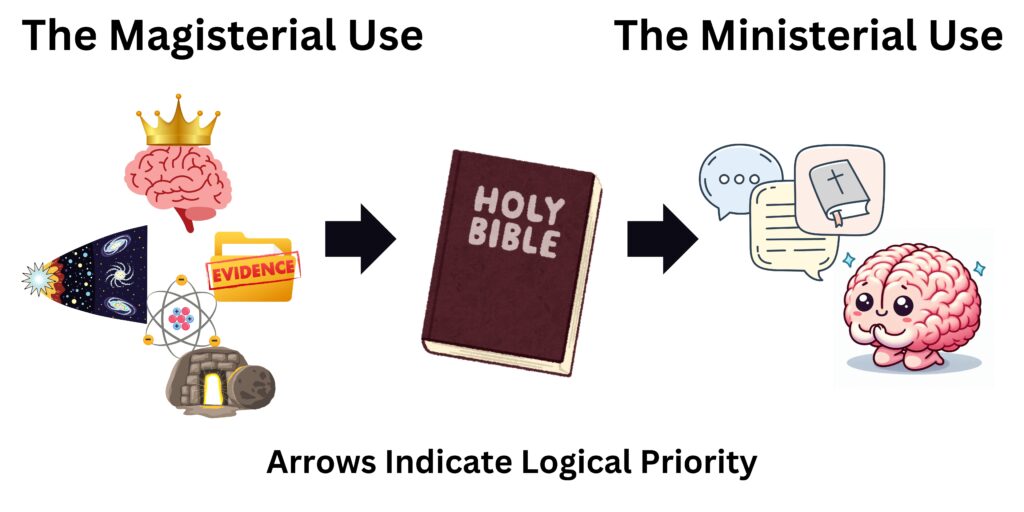

If you’ve studied theology or apologetics for a length of time, you may have come across the “Magisterial VS. Ministerial Use of reason” dichotomy. Explained briefly, A “magisterial” use of reason is where our reason is placed above the authority of the scriptures, and we then judge them on the basis of arguments and evidence. A “ministerial” use of reason is where we use our reason in submission to the authority of the scriptures. Sometimes the latter will also be called “The instrumental use of reason”. In the former, reason reigns supreme above all, it would seem, while the latter is an employment of reason to best understand what God has revealed to us.

For a long time, I struggled with this. The Bible is God’s word after all. 2 Timothy 3:16 says “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness,” (NIV) This would include not only The Old Testament scriptures that Paul (who I believe wrote 1 Timothy) studied as a Pharisee, but the New Testament writings as well. For as 2 Peter 3:15-16 says “Bear in mind that our Lord’s patience means salvation, just as our dear brother Paul also wrote you with the wisdom that God gave him. He writes the same way in all his letters, speaking in them of these matters. His letters contain some things that are hard to understand, which ignorant and unstable people distort, as they do the other Scriptures, to their own destruction.” (NIV, emphasis mine in bold). The apostle Peter, in saying “Some people distort Paul’s writings as they do the other scriptures” clearly implies that he believed Paul’s writings were on a part with the Old Testament. And, moreover, Paul considered at least the gospel of Luke to be scripture for in 1 Timothy 5:17-18, we see Paul quoting the gospel of Luke verbatim and he refers to them both as scripture. All scripture comes from God The Holy Spirit, both testaments, and because it comes from the infallible God of truth, it would seem that the ministerial use of reason would be the most appropriate for the Christian, right? But then, what is evidential apologetics if not employing the magisterial use of reason to judge whether The Bible can even be trusted in the first place?

As I’ve reflected on my own reasoning process, I’ve come to the conclusion that this is a false dichotomy. I think both the magisterial and ministerial use can and should be employed by the Christian, but it depends on where you are in terms of the logical priority of your reasoning. Logical priority is a philosophical concept that uses temporal language, and it can be a little tricky for the average person to grasp. However, philosopher Kirk MacGregor has a great real world illustration that can make this otherwise lofty concept accessible.

Dr. MacGregor writes;

“I live in Kansas. Suppose I traveled on I-35 from Kansas over the Oklahoma state border. The interstate speed limit in Kansas is 75 mph, but the interstate speed limit in Oklahoma is 70 mph. Suppose I was going 75 in Kansas and did not slow down before crossing the border. It is now simultaneously true that I am in Oklahoma, I am subject to Oklahoma’s speed laws, and I am speeding. There never was a temporal moment when only one or two of these three facts were true. Now let’s suppose that, five minutes before I entered Oklahoma, the fourth dimension of the universe collapsed, such that time ceased to exist. There would still never be a timeless moment when only one or two of the aforementioned facts were true. Either in time or in eternity, it is simultaneously true that at one and the same literal moment I am in Oklahoma, I am subject to Oklahoma’s speed laws, and I am speeding.

However, what is the logical relationship between these facts? Clearly there is a logical order or structure. I would not be subject to Oklahoma’s speed laws if I were not in Oklahoma. Hence, my being in Oklahoma is logically prior to my being subject to Oklahoma’s speed laws. And I would not be speeding if I were not subject to Oklahoma’s speed laws. Hence, my being subject to Oklahoma’s speed laws is logically prior to my speeding. Hence we have a logical structure composed of three logical moments:

1: I am in Oklahoma.

2: I am subject to Oklahoma’s speed laws.

3: I am speeding.” [1]Kirk MacGregor, “Logical Moments & The Structure Of God’s Knowledge”, October 8th 2018, FreeThinking Ministries — … Continue reading

For me, the question regarding the use of the ministerial use of reason always came down to “But why submit our reason to The Bible unless we first know The Bible is a book worthy of such submission. Why not do this with the Quran or The book of Mormon or any other scribbles claiming to be divine revelation? Shouldn’t we examine arguments and evidence to determine which texts our brains should bow down to first?” Logically prior to the ministerial use of reason, I have employed the magisterial use of reason to determine that God exists, that the Old and New Testaments are historically reliable, and that even using the most restrictive forms of historical methodology (i.e a Minimal Facts approach), we can affirm that Jesus claimed to be God, died on the cross, and rose from the dead. I’ve examined arguments against Christian theism such as The Problem of Evil, for example, and have found them wanting. After all is said and done, it does seem that The Bible really is from God as it claims. Logically posterior to such a conclusion. [2]For articles on the arguments and evidence for the reliability of the gospels and the historical claims about Jesus, see my 11 part article series “The Case For The Reliability Of The … Continue reading Check out footnote No. 2 for resources on why we should believe The Bible.

Logically posterior I employ the ministerial use of reason. This is why I resisted affirming biological evolution for much of my Christian life. Convinced that The Bible was true, and interpreting Genesis 1-3 in the way that I did, I was convinced that if evolution were true, then The Bible was wrong. It was only after I did further study and concluded that Genesis 1-3, when interpreted in its Ancient Near Eastern context and original language, taught views that left the door open for evolution, that I decided to re-open the examination of the scientific evidence and see where it lead. And this time, I ended up concluding that the fossil and genetic evidences make common descent vastly more probable than not. But prior to this, based on my pre-commitment to scripture, I would find all sorts of ways to re-interpret the scientific evidence to fit a no-evolution view. [3]For readers interested in how I interpret the creation account and how I view Adam and Eve, I recommend reading my essays “Genesis 1: Functional Creation, Temple Inauguration, and Anti-Pagan … Continue reading

This also goes for things I don’t quite understand. When I looked into the philosophical work of Dr. William Lane Craig, I found some very satisfying ways of seeing how the incarnation and The Trinity could be logically coherent. [4]I defend his Neo-Apollonarian view of the incarnation in my video “Is The Incarnation Logically Coherent?” and I defend his Social Trinitarian model in my video “Is The Doctrine Of … Continue reading But prior to coming to these very plausible philosophical models, I wasn’t sure how to wrap my mind around these issues. I believed them anyway, because The Bible taught them. [5]See, for example, my three-part response to The Watchtower Society. “Why You Should Believe In The Trinity: Responding To The WatchTower (Part 1)”, “Why You Should Believe In The … Continue reading I still don’t fully understand these doctrines and it would be hubris to say that I did, but I understand it enough to know that the incarnation and The Trinity are logically coherent concepts. In the logical moment in which the ministerial use of reason is at play, when it comes to these doctrines, all I care about are 2 things, (1) Does The Bible teach it, (2) Is it logically coherent? If I can answer these questions in the affirmative, that is enough for me. In this logical moment, I have what St. Anselm called a faith that seeks understanding.

And so when it comes to the knowledge of God, this is how my brain operates. And it’s why, despite being an evidentialist, you will often hear me swear a firm allegiance to the word of God, that what The Bible teaches is absolutely authoritative, and as Pastor Chad at Powdersville First Baptist likes to say “If it goes against The Bible, it’s wrong.” I’m not being inconsistent, I’m just saying these things in a different logical moment than in the moment in which I consider whether or not The Bible is even worthy of such allegiance. Once I’ve determined that The Bible is true, it then just becomes a matter of reading it, correctly interpreting it, and believing what it teaches.

Evidentialism – How We Know Christianity Is True

I’ve dropped the term “evidentialism” a few times now. This is my epistemology on the left hand side of the chart above. When it comes to the question of how we know Christianity is true (which encompasses our trust of The Bible), there are four major views; evidentialism, fideism, Reformed Epistemology, and presuppositionalism. Alvin Plantinga defines “fideism” as “the exclusive or basic reliance upon faith alone, accompanied by a consequent disparagement of reason and is used especially in the pursuit of philosophical or religious truth”. The fideist therefore “urges reliance on faith rather than reason, in matters philosophical and religious”, and therefore may go on to disparage the claims of reason. [6]Plantinga, Alvin (1983). “Reason and Belief in God” in Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff (eds.), Faith and Rationality: Reason and Belief in God, page 87. (Notre Dame: University … Continue reading Reformed Epistemology asserts that belief in God and/or Christianity is a properly basic belief. As for Reformed Epistemology, Dr. John Messerly writes “Properly basic beliefs (also called basic, foundational, or core beliefs) are, under the epistemological view called foundationalism, the axioms of a belief system. Foundationalism holds that all justified beliefs are either basic—they don’t depend upon other beliefs—or non-basic—they do derive from one or more basic beliefs. In the philosophy of religion, reformed epistemology is a school of thought concerning the nature of knowledge as it applies to religious beliefs. Central to Reformed epistemology is the proposition that belief in God is “properly basic” and, therefore, it doesn’t need to be inferred from other truths to be rationally warranted.” [7]Dr. John Messerly, Reasoning and Meaning, “Faith and Properly Basic Beliefs”, March 3rd 2020, — https://reasonandmeaning.com/2020/03/03/faith-and-properly-basic-beliefs/ Reformed Epistemology has debates even within itself. For example, as David Pallmann explains in episode 119 of The Cerebral Faith Podcast, Alvin Platinga’s epistemology differs from that of William Lane Craig’s. [8]See The Cerebral Faith Podcast, “Episode 119: Is Belief In God Properly Basic? – With David Pallmann and Caleb Jackson”. There’s also a whole debate on the validity of externalism and internalism, which would take us way too far afield to explore here. Thinkers like William Lane Craig would say that arguments and evidence are valuable in SHOWING skeptics that Christianity is true, but that they aren’t necessary in KNOWING that Christianity is true. In knowing that Christianity is true, Dr. Craig would say that all we need is the inner witness of The Holy Spirit testifying to us that the scriptures before us are true. [9]See “Philosophical Foundations For A Christian Worldview” by William Lane Craig and J.P Moreland, InterVarsity Press, Chapter 7. I disagree with both Plantinga and Craig, and prefer evidentialism. Evidentialism is defined by philosopher Lydia McGrew in the following way; “When I speak of evidentialism, I’m speaking in the realm of apologetics and the philosophy of religion. There’s a larger position known as evidentialism in philosophy, which covers all topics. But here, I’m speaking of it specifically with respect to the question of the existence of God and the truth of Christianity. …Evidentialism is the position that the existence of God and the specific theological propositions of Christianity require evidence for their support and that this evidence is available. …The evidentialist … does not believe that Christianity can be known to be true directly without any reasons, that it’s not the kind of thing that you could just sort of wake up one morning and bang, you know, ‘I know that Christianity is true’, at least not in this life. Maybe in direct beatific vision of God after this life, but as things are now, it’s the kind of thing that requires reasons. But at the same time, the evidentialist says that God has made evidence available to us, on the basis of which we can be justified in thinking that God exists and that Christianity is true.” [10]Lydia McGrew, “What Evidentialism Is and Isn’t”, a talk delivered on January 20, 2015 at the Western Michigan University Chapter of Ratio Christi. — … Continue reading

One major objection to evidentialism is that it would reduce most of The Church to irrationality. Many Christians haven’t or can’t take the time and rigiously study the evidence for and against their view. They either don’t know that there are arguments for the truth of Christianity, or they have little time, or what have you. So are these people irrational if they believe? I don’t think so. Dr. McGrew employs two categories that are helpful; explicit rationality and implicit rationality. People like me and many others in the apologetics community are explicitly rational. We’ve looked at the arguments and evidence deeply and have come to the conclusion that Christianity is true. You can clearly articulate in very sophisticated ways why you believe what you believe. That is to say, we’ve studied Christian Apologetics and its opponents. Implicit Rationality is what I suspect most Christians have. Most Christians, if you ask them why they believe Christianity is true, might say “I just can’t believe this beautiful, complex world is a result of chance.” or “Just look at the complexity of the human body. Do you think this is an accident? The human brain alone is more complex than anything the most brilliant scientists have made.” Or, when you read the gospels, you might just get the sense “Hey, this reads like historical reportage. It’s like it was written by people who were there.” I had a co-worker once say that while he wasn’t a Christian, he couldn’t be an atheist either because, in his words, “This world is too beautiful not to be the work of a great artist.” At 6 years old, I reasoned “Why does anything at all exist? The world exists for a reason. Well, because God created it. If God didn’t exist, nothing else would either. What if God didn’t exist? Then nothing would exist! Nothing COULD exist!” Now, none of these types of statements would stand up in a debate against an atheist, but all of them express some sort of reason to believe. And, in my opinion, all of these are crude forms of arguments that actually work. For example, 6-year-old me was treading on a crude form of what I would later learn is “The Contingency Argument For God’s Existence”. Some of these are teleological arguments. And if you do the heavy lifting, you’ll find that the gospels are indeed eyewitness testimonies. Erik Manning of Testify has a great video on this distinction on his channel called “Do You Need Apologetics To Have A Rational Faith?” where he also mentions the explicit/implicit rationality distinction.

Why I’m an evidentialist rather than a reformed epistemologist really boils down to the fact that no matter how much of a charitable ear I try to give to folks like Dr. William Lane Craig and Alvin Plantinga, it really seems like what they’re promoting isn’t too dissimilar to the “burning of the bosom” epistemology that the Mormons espouse. If you ask a Mormon how one can know that Mormonism is true, he will tell you to just pray about it and ask God to reveal it to your heart. Ok, but what do we do if I pray about it and I feel like God is leading me away from Mormonism and into Nicene Christianity? How do I know if my burning bosom is reliable and His isn’t? Well, looking at objective arguments with evidence that can support the premises would be a pretty good tiebreaker. But then, we’re back to an evidentialist epistemology! Moreover, personally, when I first started doubting my faith at 18, it was precisely a powerful subjective experience with God that I used as justification in my conversations with atheists. They dismissed my religious experience as being the product of brain chemistry brought on by my circumstances. I experienced God’s presence because I needed to. It was basically all in my head. That, combined with half a dozen “How do you know?” questions, and all of a sudden I found myself spiraling into agnosticism until God providentially introduced me to Lee Strobel’s “The Case For Christ”. Although Craig uses classical and evidential apologetics in his presentations, on the basis of his knowing VS. showing distinction, what do you do with a doubter who himself needs to be shown that Christianity is true? Well, Dr. Craig has defended that the witness of The Holy Spirit can be a defeater-defeater. Again, I don’t agree. Now, as I said in the podcast episode with David Pallmann and Caleb Jackson, [11]Again, check out The Cerebral Faith Podcast, “Episode 119: Is Belief In God Properly Basic? – With David Pallmann and Caleb Jackson”. I think belief on the basis of some experience of God or the Spirit’s inner witness can be grounds for rational belief in the absence of a defeater. And David Pallmann nicely said that religious experience can serve as a sort of prima facie evidence for God. But, I would disagree with Craig that if you’re presented with an explicit potential defeater (e.g The Problem of Evil) then you would still be rational in continuing to believe, even if you didn’t have a counter-argument for the defeater. How would faithfulness be distinguished from just a refusal to follow the evidence where it leads? And so, going back to my experience, I would hold that I was certainly rational in affirming my Christian faith on the basis of my radical experience with God (and subsequently transformed life) but when the atheists I was trying to evangelize brought up potential defeaters to my worldview, had I continued believing without finding answers, then I would have been thinking irrationally.

Does The Bible Endorse An Evidentialist Epistemology?

I think it does. 1 Kings 18 records a contest between Elijah and the prophets of Baal. Both Elijah and the prophets of Baal set up alters to their respective gods. Elijah determined what the results of the contest would be; whoever lights the fire of the alter is God and should be followed (verse 21). Whoever doesn’t is a false god and should be rejected. As you read 1 Kings 18, you read that the prophets of Baal did all sorts of theatrics all day long to get Baal’s attention (verses 26, 28-29), resulting in the famous meme-able statement by Elijah that Baal was probably too busy relieving himself (verse 27). Afterwards, Elijah’s alter to Yahweh was set up and he commanded it be drenched in water. Because, after all, if you can set something on fire that’s been drenched in water several times, that’s just an extra flex (verses 30-35). Then Elijah prayed to God, and whereas the prophets of Baal cried out to him all day long, Elijah only prayed once. When he did, fire fell down and consumed the alter (verses 36-38). Yahweh had won the contest. Baal had lost. Now, this contest has evidential value to the Israelites. Look at how powerful God is to consume even a wet pile of wood! Look at how swift He is to respond to prayer! Yahweh is so much better than Baal! But imagine if Elijah said “I know Baal seems like a pretty good god to follow, but you gotta believe me! Yahweh is so much better! Just have faith! Ask God to reveal to your hearts the truth!” Do you think that would have had the same effect as the contest that was actually held between Elijah and the prophets of Baal? I don’t think so. Neither did Elijah say something like “You know God exists, you’re just suppressing the truth.” He gave evidence.

In John 10:37-38, Jesus says “Do not believe me unless I do the works of my Father. But if I do them, even though you do not believe me, believe the works, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me, and I in the Father.” (NIV, emphasis mine in bold). Jesus was telling those listening to Him not believe in him unless He did the works of His Father. Of course, Jesus was doing the works of His Father which would include all of his healing miracles as well as fulfilled messianic prophecies, but the point is that Jesus is saying not to just believe in him unless they have good grounds to do so. Jesus’ miracles and his fulfillment of Old Testament prophesies served as strong evidence to the people at the time that he truly was who he claimed to be. Even after the resurrection, Jesus stayed with His disciples for an additional forty days and provided them with “many convincing proofs” that He was resurrected and was who He claimed to be (see Acts 1:2–3 NIV). Jesus understood the role and value of evidence and the importance of developing an evidential faith.

In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul was addressing a heresy that arose in the Corinthian church that there would be no resurrection of anyone. He makes the modus tollens argument that if the dead aren’t raised, then Christ hasn’t been raised either, and if Christ hasn’t been raised, Christianity is a waste of time. But, given that Christ has been raised, it follows that the dead will be raised and Christianity is not, in fact, a waste of time (see verses 12-22). To support the premise that Christ has been raised, he cites a creed that he received and had previously passed onto them (verse 3). This creed states that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures, was buried, and was raised. Paul goes on to cite postmortem appearances to many people including The Twelve, 500 people, and Paul himself. (verses 4-8). He appeals to the testimony of eyewitnesses who are still alive and can be interviewed. Paul never once says “Jesus is alive. Just trust me bro. Pray about it. God will reveal it to your hearts if Jesus is risen from the dead.” He never says “You know Jesus is risen from the dead. You’re just suppressing the truth!” No, he says “Jesus is risen. I’ve seen him, his disciples have seen him, heck even 500 people saw him at one time. Some of these guys have died, but most are still alive. Don’t take my word for it. Go talk to them yourselves.”

One famous proof text against an evidentialist epistemology is John 20:29. In this passage, Jesus has just appeared to Thomas who was so skeptical that Jesus was alive that he said he would not believe unless he put his fingers in his crucifixion wounds (John 20:25). Later, Jesus shows up, invites Thomas to put his fingers in his hands and sides, and admonishes him to stop doubting and believe. (John 20:26-27). Thomas calls Jesus God with no rebuke from Jesus (John 20:28), and then Jesus says “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.” (John 20:29, NIV) Fideists love this passage because at first glance it seems to support their view that you should believe without evidence. Thomas demanded hardcore proof and here, it would seem, Jesus is rebuking him for that. So why doesn’t this passage persuade me to be a fideist? First, John 20:29 as a proof text for fideism is that Jesus only says this after giving Thomas the evidence he demanded! The very preceding verses tell us that Jesus appeared before Thomas and invited him to put his finger in His hands and side (verses 26-27). If Jesus were against having evidence for belief, I would think we would only have the rebuke, and not an offer from Jesus to actually get the requested proof. Secondly, In Acts 1:3, we read “After his suffering, he presented himself to them and gave many convincing proofs that he was alive. He appeared to them over a period of forty days and spoke about the kingdom of God.” (NIV, emphasis mine in bold.) Moreover, Jesus himself said His resurrection would be a sign; specifically the sign of Jonah (Matthew 12:39). During his ministry, as we saw above, Jesus said not to believe him unless he did the works of his Father (John 10:37-38). How can Jesus be against evidence when he gave it all the time? A principle of the grammatical-historical method of exegesis is to interpret scripture in light of scripture. In light of the passages where Jesus gives evidence, it is unlikely we should interpret John 20:29 as being in favor of a blind faith. Thirdly, no one after the first century has seen the risen Christ. He ascended into Heaven (Acts 1:7-11). Even those who believe in the resurrection of Jesus on the basis of evidence haven’t seen Jesus with their own eyes! Christians might believe Christ is risen on the basis of a Minimal Facts Argument or a Maximal Data Argument, and these arguments do give good justification for affirming the historicity of the event, but not even the strongest apologetic for the resurrection comes anywhere close to what Thomas had! I think the most likely interpretation of Jesus’ words is that the apostles shouldn’t let their privileged epistemic position go to their heads. They believe in Jesus because they saw him with their own eyes, but Jesus says that those of us who believe without that ultimate standard of proof are no less blessed.

Conservative VS. Liberal Views. Who Cares?

I would consider myself to be a conservative Christian. I hold that The Bible is inspired and is inerrant in everything that it intends to teach. I few years ago, I read through the Chicago Statement on Inerrancy and I agreed with 99% of the affirmations and denials. That 1% I couldn’t agree with was due to the fact I wasn’t sure what those tiny handful affirmation/denials were asking of me. I thought “It depends on what you mean by that.” I use the Grammatical-Historical method of hermenuetics which I made a whole blog series on. [12]Click here if you’re interested. And yet, I hold to certain views that some would classify as being “liberal” and others would classify as being “conservative”. Those that would be deemed more liberal might be my affirmation of Theistic Evolution and a “non-literal” view of Genesis 1 and a “non-literal” view of Adam and Eve’s formation in Genesis 2. There’s also my belief in conditional immortality (or more commonly known as Annihilationism).

But the thing is, my view on the inerrancy and authority of The Bible hasn’t changed throughout my entire Christian life, nor have I adopted any other method of interpretation. I may share a conclusion or two with someone deemed to be “liberal”, but I guarantee you that we didn’t come to our conclusions in the same way. A Progressive Christian, for example, might be a Theistic Evolutionist because “Science says evolution is true. And you know, The Bible gets things wrong sometimes. After all, it’s just a bunch of man-made books trying to describe their experiences with God.” A Progressive might reject the eternal torment of Hell because “A loving God would NEEEEEEVER do that.” Whereas in my case, I consistently submitted my reason to the authority of God’s word and only jumped ship on these two examples of “conservative” views when my exegesis and further studies lead me in other directions.

I hold plenty of conservative positions though. I think marriage is to be between one man and one woman for life (Genesis 2:24) and that it is a sin for two people of the same gender to have sex (Romans 1:26-27, 1 Corinthians 6:9-11, 1 Timothy 1:9-11). Speaking of gender, there are only two of those and which one you are is determined by your biology. “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” (Genesis 1:27, NIV) And sex should be held off until marriage as Song Of Solomon 8:4 and Hebrews 13:4 says. Also, my very commitment to the inerrancy and authority of scripture is itself a conservative position. Just read Progressive Christian literature and see how much they throw The Bible under the bus when it contradicts their woke theology.

At the end of the day, I really don’t care what label you attach to any of my theological positions. I care about whether or not they’re true! I want to know the truth and then live as though the truth were true! If it’s true, I’ll affirm it, even if I share that position with the shouting angry fundamentalist preacher. If it’s true, I’ll affirm it even if it gives me common ground with the pink-haired woke theology professor. If it’s true, I’ll affirm it even if it gets me in hot water with both the right and the left. Guilt by association shouldn’t drive us away from a position. Only good refutations should do that. Call me a conservative if you like. Call me a liberal if you like. But I affirm The Apostles, Nicene, and Athanatian creeds, so one thing you must not call me is a heretic.

Conclusion

“I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now.” (John 16:12, ESV). I love it when Tim McGrew does this at the end of conference talks. Sorry, I had to do it at least once. This is my theological epistemology.

References

| ↑1 | Kirk MacGregor, “Logical Moments & The Structure Of God’s Knowledge”, October 8th 2018, FreeThinking Ministries — https://freethinkingministries.com/logical-moments-the-structure-of-gods-knowledge/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For articles on the arguments and evidence for the reliability of the gospels and the historical claims about Jesus, see my 11 part article series “The Case For The Reliability Of The Gospels”. This is a muti-part article series meant to be read in order. It’s pretty in-depth and I often jokingly like to say that I wrote a book and put it on the blog. It defends Christianity’s historical claims from what philosopher Lydia McGrew calls “A Maximal Data Approach”. If you’d like something less in-depth, but still within the methodology of MDA, check out my article “The Gospel Eyewitness Argument For Jesus’ Resurrection.” For a much stricter historical metholody, check out my article “The Minimal Facts Case For Jesus’ Resurrection – PART 1” and “The Minimal Facts Case For Jesus’ Resurrection – PART 2”. As I explain in the aforementioned article, the resurrection of Jesus is of particular epistemic importance as Jesus claimed to be God. If Jesus claimed to be God and then died and rose from the dead, then that it pretty good evidence that he was telling the truth. God would not raise a heretic and a blasphemer. If Jesus were merely a man, and then God raised him, that would lead people to believe in him! People all over the world in fact. It would behoove God to keep the one who tried to steal his identity dead in the ground. But if Jesus did rise, then God The Father put his stamp of approval on Jesus’ ministry. It verifies that Jesus is who he claimed to be. Now, if Jesus is God as his resurrection vindicates, then that means what Jesus taught carries a lot of weight. So, for example, that Jesus quoted from the Old Testament as though it were inspired and authoritative carries a lot of weight. Who would be in a better position to know if the Old Testament were from God than God Himself? If you are a skeptic, or a doubter, or a Christian wrestling with his faith, I highly recommend checking these articles out. |

| ↑3 | For readers interested in how I interpret the creation account and how I view Adam and Eve, I recommend reading my essays “Genesis 1: Functional Creation, Temple Inauguration, and Anti-Pagan Polemics” and “Genesis 2 & 3: Adam and Eve as Archetypes, Priests In The Garden, and The Fall”. And if you’d like, I also have given conference-style talks in my live streamed videos “Genesis 1 – How The ANE Context Solves The Science/Faith Controversy” and “Genesis 2: Archetypes, Priests In The Garden Of Eden, and The Creation/Evolution Debate”. |

| ↑4 | I defend his Neo-Apollonarian view of the incarnation in my video “Is The Incarnation Logically Coherent?” and I defend his Social Trinitarian model in my video “Is The Doctrine Of The Trinity Logically Coherent?” |

| ↑5 | See, for example, my three-part response to The Watchtower Society. “Why You Should Believe In The Trinity: Responding To The WatchTower (Part 1)”, “Why You Should Believe In The Trinity: Responding To The WatchTower (Part 2)”, and “Why You Should Believe In The Trinity: Responding To The WatchTower (Part 3)”. |

| ↑6 | Plantinga, Alvin (1983). “Reason and Belief in God” in Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff (eds.), Faith and Rationality: Reason and Belief in God, page 87. (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press). |

| ↑7 | Dr. John Messerly, Reasoning and Meaning, “Faith and Properly Basic Beliefs”, March 3rd 2020, — https://reasonandmeaning.com/2020/03/03/faith-and-properly-basic-beliefs/ |

| ↑8 | See The Cerebral Faith Podcast, “Episode 119: Is Belief In God Properly Basic? – With David Pallmann and Caleb Jackson”. |

| ↑9 | See “Philosophical Foundations For A Christian Worldview” by William Lane Craig and J.P Moreland, InterVarsity Press, Chapter 7. |

| ↑10 | Lydia McGrew, “What Evidentialism Is and Isn’t”, a talk delivered on January 20, 2015 at the Western Michigan University Chapter of Ratio Christi. — https://apologetics315.com/2015/02/what-evidentialism-is-and-isnt-mp3-by-lydia-mcgrew/ |

| ↑11 | Again, check out The Cerebral Faith Podcast, “Episode 119: Is Belief In God Properly Basic? – With David Pallmann and Caleb Jackson”. |

| ↑12 | Click here if you’re interested. |

Discover more from Cerebral Faith

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.