Hey Evan I’m a young Christian wanting to build my faith up in Christ. After looking I found one of the reasons many younger people may leave the faith is because they couldn’t believe in biblical Innerarncy anymore. Personally I do not not stock my faith on Innerarncy but on the ressurection of Christ. However I wanted to ask after studying the Bible for years how do you view the doctrine of Innerarncy? How should a young Christian view this doctrine. Also even if one were to give up the doctrine of Innerarncy shouldn’t the scriptures still be viewed as Inspired and authoritative in a believers life and practice, cause I see some people who don’t believe in Innerarncy tend to not only lower the Bible’s authority but sometimes completely disregard it (such as allowing obviously sinful practices to be normal) Would love to hear your wisdom thanks!

Hey Evan I’m a young Christian wanting to build my faith up in Christ. After looking I found one of the reasons many younger people may leave the faith is because they couldn’t believe in biblical Innerarncy anymore. Personally I do not not stock my faith on Innerarncy but on the ressurection of Christ. However I wanted to ask after studying the Bible for years how do you view the doctrine of Innerarncy? How should a young Christian view this doctrine. Also even if one were to give up the doctrine of Innerarncy shouldn’t the scriptures still be viewed as Inspired and authoritative in a believers life and practice, cause I see some people who don’t believe in Innerarncy tend to not only lower the Bible’s authority but sometimes completely disregard it (such as allowing obviously sinful practices to be normal) Would love to hear your wisdom thanks!

– Josh

I definitely agree that we should pull our full stock in the work of Christ through His death and resurrection. As I explain in my 10 part blog post series, and in my book “My Redeemer Lives”, there is an overabundance of historical evidence for the death and resurrection of Jesus. If Jesus is raised, then Christianity is true, even if you think you’ve found a factual error or two in The Bible.

I definitely agree that we should pull our full stock in the work of Christ through His death and resurrection. As I explain in my 10 part blog post series, and in my book “My Redeemer Lives”, there is an overabundance of historical evidence for the death and resurrection of Jesus. If Jesus is raised, then Christianity is true, even if you think you’ve found a factual error or two in The Bible.

I myself am a biblical inerrantist. I believe The Bible is factually correct in every area that it intends to teach. It’s inerrant in everything it affirms. It does trouble me to see Christians such as Gregory Boyd and Peter Enns forfeit this doctrine, but I would rather them be Christians who deny inerrancy than atheists who deny inerrancy. I think that we as Christians ought to be willing to step up to the plate and defend the inerrancy of The Bible. However, I also think we ought not make a bigger deal out of it than it needs to be. Inerrancy is important, but it’s nowhere near as important as the existence of God, the death and resurrection of Jesus, etc. All truth is important, but some truths are more important than others. God’s not going to fall off His throne if inerrancy is false.

But like you said, I likewise see a denial of inerrancy as a slippery slope. This is why I consider it important. Once someone thinks the biblical authors are mistaken in places, what’s to stop them from cherry picking what parts they want to believe and what parts they want to jettison? What’s to stop a Christian pressured by the LGBT crowd to say, “You know what? The Apostle Paul was a man of time. Even though he writes in his epistles that homosexuality is a sin, I just think he was mistaken. We’re much more enlightened now.”?

Therefore, I think we ought not give up inerrancy unless we absolutely have to.

Gregory Boyd actually has a book in which he actually tries to argue that a Bible with errors makes for a powerful argument that it’s inspired! It’s called “Inspired Imperfection: How The Bible’s Problems Enhance Its Divine Authority”. Now, I haven’t gotten a chance to read the book, so I have no idea how he makes a connection between errancy and divine authority, but I thought it was worth a mention.

I think a HUGE reason that people reject biblical inerrancy is that they have their own ideas about how we got The Bible (i.e how inspiration works), and they have their own ideas for what counts as an error. If you have a particular idea of how The Bible got created and that idea gets challenged by what you see in the text or what you see biblical scholarship saying, you might errantly conclude “Well, I guess The Bible’s not really inspired after all!” A lot of us have what Dr. Michael Heiser often calls “A Magical Download view of inspiration” where The Holy Spirit, in a sense, posesses the biblical author, they go in a trance, and they just start jotting things down that The Holy Spirit wants them to say. Then they wake up and go “Wow! I wonder what I wrote on this papyrus while I was out!” Now, none of us consciously think of inspiration in this way, but if pressed, I think a lot of us subconsciously view the process like this. So when we see very human elements in the text, it bothers us, and we feel the need to deny a divine authorship behind the text or we just come up with all sorts of ad-hoc and contrived explanations for how what we think we see in the text isn’t really there.

So, for example, when you look at 2 Peter and Jude and find a heavy reliance on pseudepigraphical works like 1 Enoch which itself derives from a Greek work (see my paper “Genesis 6 – Descendents Of Cain, Neanderthals, Ancient Kings, Or Angel-Human Hybrids” for more on this), if you have the idea that Peter and Jude were just getting their info completely downloaded from God and didn’t rely on any source materials, that can be a faith shattering realization!

Another example can be found in Jesus’ own sermons. We think to ourselves “Surely everything Jesus said was original. He’s God incarnate! So He must just pontificate 100% new and totally unheard of revelation.” Well, if you think that, you’re going to have a crisis of faith when you learn that several of Jesus’ teachings were in line with rabbinic teachings of The Second Temple period, particularly the essenes (which is why some scholars think Jesus might have been an essene). Phil Weingart talks about this in depth in his book “The Rabbi On The Mount” which I highly recommend. That isn’t to say Jesus just regurgitated essence or Second Temple Period rabbinic theology all of the time, he didn’t. But there are points of contact.

The Bible is a human book. Yes, it is a human book. Humans wrote it. Each author displays his own vocabulary choices, idioms of his day, and so on. This is just like any ordinary humanly written document. But it not merely a human book, it is also a divine book. The content was inspired by God.

Despite my theological grievences with Peter Enns, I do wholeheartedly agree that we ought to think of scripture similar to Jesus. He calls this “An Incarnational View Of Inspiration”. Jesus Christ was fully and truly human, but also fully and truly God. The Bible is also fully and truly from humans, but also fully and truly from God. And, like Jesus, we should avoid downplaying the human aspects in an attempt to elevate the divine aspects. We should also avoid elevating the human aspects to the extent that we give the impression that The Bible is just another ANE document among many. It’s not. It’s God breathed (2 Timothy 3:16).

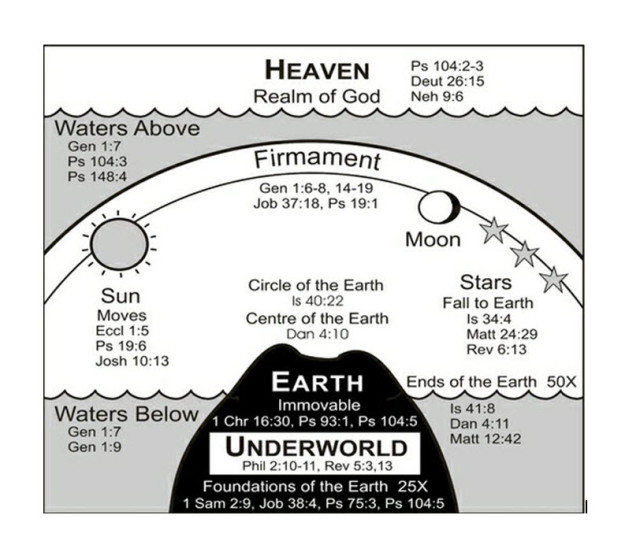

Another reason why many reject the inerrancy of The Bible is that they have mistaken ideas of what counts as an error. If one thinks that The Bible is supposed to reveal scientific information, that when it talks about the natural world, it’s descriptions should correspond to the way modern science says it is, then when you discover that The Bible is littered with what I like to call “Dome Cosmology”, you might think to yourself “The Bible is littered with scientific errors. Chuck it out.”

Of course, if you’ve read my stuff on Genesis 1 , or even just my writings on The Primeval History period in general you’ll know why I don’t consider “Dome Cosmology” to be errors. Remember what I said earlier in this article; “The Bible is factually correct in all that it intends to teach” and “It’s inerrant in everything it affirms“. I worded my articulation of inerrancy carefully. So, if The Bible is not intending to teach cosmology, biology, zoology, but does intend to accurately record salvation history, teach us how to live good moral lives, teach us theological truths (e.g the attributes of God, how to get saved, the nature of Hell, who Jesus is etc.) then the fact that we find descriptions in The Bible of the Earth being covered by a solid dome holding back waters held up by pillars shouldn’t bother us in the least. That’s only an error if one thinks, contra Galileo, that The Bible intends to teach us how the heavens go as well as how to go to Heaven.

Of course, if you’ve read my stuff on Genesis 1 , or even just my writings on The Primeval History period in general you’ll know why I don’t consider “Dome Cosmology” to be errors. Remember what I said earlier in this article; “The Bible is factually correct in all that it intends to teach” and “It’s inerrant in everything it affirms“. I worded my articulation of inerrancy carefully. So, if The Bible is not intending to teach cosmology, biology, zoology, but does intend to accurately record salvation history, teach us how to live good moral lives, teach us theological truths (e.g the attributes of God, how to get saved, the nature of Hell, who Jesus is etc.) then the fact that we find descriptions in The Bible of the Earth being covered by a solid dome holding back waters held up by pillars shouldn’t bother us in the least. That’s only an error if one thinks, contra Galileo, that The Bible intends to teach us how the heavens go as well as how to go to Heaven.

So, it’s crucial, absolutely crucial that we come to an adequate answer to the question “What counts as an error?”

One final thing I’d like to mention is this; we often may think The Bible made an error when it’s really we as the interpreters who made an error. Every time I think I’ve found a contradiction or factual error, a little bit of digging (or sometimes a lot of digging) has revealed that what I thought was a contradiction or error really wasn’t. Most so-called contradictions can easily be resolved by positing logically possible explanations or just by correctly exegeting the passages. Sometimes we think we’ve found a contradiction because one verse or the other was taken out of context to make it seem like it was saying something it wasn’t actually saying. I see the internet atheist crowd do this all the time.

Some resources I would recommend are the following:

- “The Big Book Of Bible Difficulties” by Norman Geisler and Thomas Howe

- “Why Are There Differences In The Gospels?” by Michael Licona

- John Walton’s “The Lost World Of…” series.

- Pretty much everything by Michael Heiser and Brian Godawa.

If you have any questions about Christian theology or apologetics, send Mr. Minton an E-mail at CerebralFaith@Gmail.com. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a Christian or Non-Christian, whether your question is about doubts you’re having or about something you read in The Bible that confused you. Send your question in, whatever it may be, and Mr. Minton will respond in a blog post just like this one.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

Discover more from Cerebral Faith

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.